|

The Madness of Versailles II June 20, 2000 Comment: #364 Discussion Thread: #s 61, 72, 102, 114, 117, 130, 131, 146, 154, 159, 166, 169, 184, 193, 328 References: [1] Thomas E. Ricks and Roberto Suro, "Military Budget Maneuvers Target Next President," Washington Post, June 5, 2000, Pg. 1. [2] Tom Philpott, "Plump Senate Package For Service People Likely To Be Pared," Newport News (VA) Daily Press, June 16, 2000. [3] George C. Wilson, "Duck, Soldier! Cranberries Incoming!" National Journal, June 10, 2000, Pg. 1850. [4] By John M. Donnelly, "Flag Officers Net Jetliners In New Defense Bills," Defense Week, June 12, 2000,Pg. 1. Separate Attachment: [5] Figure 1 in Adobe Acrobat Format (Free adobe acrobat reader can be downloaded from http://www.adobe.com/products/acrobat/readstep.htm Introduction and Aim Every four years, the courtiers of Versailles on the Potomac open the quadrennial fun house to lure the Presidential contenders into bidding war on defense budgets. Their aim is to lock the new President on a spending pathway of their choosing, so that the change of administrations will not disturb the life style in Versailles. But this time, the Pentagon and the Congress may be going too far. By postponing the hard decisions yet again, they are setting up the next President for a collision between the rapidly rising budget requirements of the post-cold war military and the rising social security and Medicare requirements of the bow wave of aging baby boomers. While the looming crackup has been discernable for at least ten years, the next President will be the first President faced with the need to do something about it, because his long-range budget proposals will reach well into second half of this decade. My aim in this commentary is to show how the power games of today are helping to set the stage for an unnecessary and immoral political war between different factions of society tomorrow. If this is allowed to happen, the troops at the pointy end of spear, the taxpayers, and perhaps most importantly, civilized values in a wealthy democracy will be losers. Current Events in the Versailles Fun House The service chiefs fired the opening round in the coming war in early June, when they finalized the first draft of the new six-year budget plan for Fiscal Years 2002 to 2007. The next President will inherit and submit this plan to Congress next February. On June 5, Tom Ricks and Roberto Suro reported in the Washington Post that their plan needs more than $30 billion per year than was assigned to them in their budget planning guidance last January by the Secretary of Defense [Reference 1]. Bear in mind, the $30 billion per year shortfall is measured against a budget guidance for a new plan that merely extends the budget projection of the existing plan before Congress for Fiscal Years 2001 to 2005 out to 2007. Yet, magically, $30 billion per year in unfunded requirements appeared between that old plan's submission in February and the first draft of the new plan in June. Not to be outdone, across the Potomac, the inhabitants of the "world's greatest deliberative body," aka the US Senate, joined the party in their bid to look "pro-defense" by throwing more slop to the hogs in the Versailles sausage factory. To wit - Reference 2: Tom Philpott reports the Senate voted to 95 to 2 to add a pay and benefits package (much of which will benefit retirees) which would increase spending by at least $10 billion per year for as far as the eye can see. If enacted, which is doubtful, this add-on would come on top of the $30 billion in unfunded requirements of the service chiefs. On the other hand, if the Pentagon is told to pay for the benefits package out of its hide, the stated annual shortfall rises to $40 billion per year, assuming the shortfall is real. Reference 3: George Wilson, the dean of Washington's defense reporters, tells us one reason why shortfalls exist. The Defense Subcommittee of Senate Appropriations Committee is using its own criticism of readiness problems (which are real but caused by the rising cost of low readiness, a factor no one in Congress or the Pentagon wants to address) as a distraction to justify adding money for back-home pork projects and glamorous weapons, for example, urging the military to consume more cranberries, a gambit to renege on the promise to get troops off food stamps, and a plan to force the Pentagon to continue buying Pennsylvania coal for heating plants on an AF base in Germany (under a long-term defense 'program' known affectionately in some circles as the Daniel Flood Memorial Coal Pile in memory of the porking operations by the late congressman from coal mining region of northeastern Pa). According to Wilson, slopping the hogs by Senate Republicans became so gross this year, it even blew the circuits some of their own staff analysts. One blunt staff assessment said, "Having decided to spend most additional money on major equipment items and not on readiness, the Defense Subcommittee not only left [spending money] on the table but it also disregarded the assumptions of the budget resolution" (i.e., that Congress would raise pay enough to get troops off food stamps). The assessment continued, "does this Senate-reported Department of Defense appropriations bill take full advantage of the opportunity afforded by the budget resolution to more fully address the serious readiness deficiencies created by the Clinton administration and the senior leadership of the Department of Defense? Moreover, does the bill specifically reject the Senate's 99-0 vote and implicit advice to address the issue of military food stamps?" Reference 4: John Donnelly, in Defense Week, reports how Congress is in the process of appropriating millions of dollars for executive jets to ferry around generals, admirals, and other VIPs, despite a audit just issued by its own investigative arm, the General Accounting Office, that says the Pentagon has not even justified adequately the requirement for the 391 "operational support aircraft" the military now owns. Putting the Madness into Perspective Read separately, each of these reports is titillating, but what do they imply about the total defense budget? Figure 1 helps us to appreciate the madness enveloping Versailles.

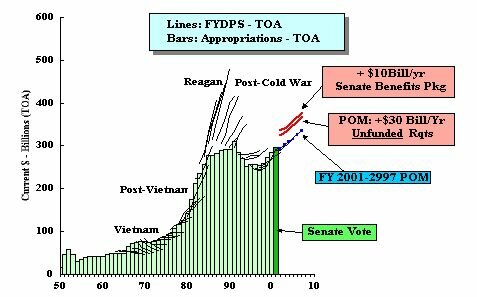

Figure 1 compares the first draft of the new six year budget plan (the 'blue line' known as the POM - explained below) to all past budget plans (the 'black' lines) dating to publication of the Defense Department's first long range plan in 1962 (for Fiscal Years 1963 to 1967), as well as the actual appropriations by Congress (denoted by the 'light green bars') and the recent Senate vote (the 'dark green bar'). The lower "red" line portrays the implications of the $30 billion in unfunded annual requirements and the upper 'red' line adds the pay and benefits package just voted by the Senate (assuming $10 billion per year). [ Figure 1 is also portrayed separately in Attachment 5 in Adobe Acrobat Format. A free Adobe reader can be found at the hot link referenced above.] The long-range budget plans in Figure 1 are not produced by a few planners in a back room. The 'black lines' evolve out of the machinations of thousands of people engaged in a complex bureaucratic process known in the Pentagon as the Planning, Programming, and Budgeting System (PPBS), which consumes millions of man-hours of time each year. Before discussing what Figure 1 tells us, we should understand how it fits into the context of the PPBS-driven decision process in the Pentagon. The PPBS in Theory: Each PPBS cycle begins with a strategic planning phase that is supposed to include an analysis of nationals goals and threats to those goals. In theory, this effort permits planners to identify a military strategy to counter the threats. The strategy phase usually ends in late winter when the Secretary of Defense issues a strategic guidance document to the military services. This document includes a long-range fiscal guidance that tells each service or independent defense agency how much money it should plan for in each year of the long-range plan. The PPBS now transitions into a second phase, or programming phase, which begins when the services respond to the guidance in May with a draft budget plan, known as the Program Objectives Memorandum or POM (the first draft of the new FYDP). The POM, describes the all the forces and supporting programs (like R&D or training) the military services believe they need to execute the strategy. Taken literally, in terms of the POM's location in this logical structure, the main message in Ricks's and Suro's report in Reference 1 is that the service chiefs do not think their POMs can execute the strategy unless the fiscal guidance is increased by $30 billion per year. But the POM is only the first draft of the new plan. The remainder of the year becomes a complex bureaucratic negotiation between the Secretary of Defense and the military services to convert the POMs into a second and then a third (final) draft of the Future Years Defense Plan, or FYDP. The first year of the FYDP then becomes the President's budget proposal to Congress in January and its future years are a roadmap of where that budget will take us, if enacted. Although there have been substantial procedural modifications over time, the Secretary of Defense has used some variation of a step-by-step methodology to build the Defense Department's FYDPs since 1962, all of which are portrayed in Figure 1 by the horsehair-like 'black lines.' The PPBS in Action: The shifting pattern of long-range budget plans in Figure 1 can thought of as a snapshot of the outward manifestations, or macro-dynamics, of all these PPBS activities. The history of these macro-dynamics helps us to understand how well-established systemic behavior patterns, or the habitual modes of conduct of thousands of people, are creating a budget crisis. Starting with Vietnam period, the lines in Figure 1 show that planners projected decreasing budgets during each FYDP, but note how each succeeding FYDP raised those future budgets above the levels of its predecessor. So each FYDP during this period was "underfunded" in terms of its succeeding FYDP. This dynamic suggests an unplanned buildup of cost pressures inside the FYDP. With the end of the Vietnam War, one would expect that planners would project even steeper reductions in future budgets, because the need to finance military operations was reduced. But note how planners stopped projecting declines in future budgets, and with only a two insignificant exceptions (the first years of Carter administration), planners produced a succession of FYDPs which assumed accelerating rates of growth in future budgets, suggesting not only a continuation of cost pressures, but a rapid build up of these pressures. Bear in mind, forces were shrinking during much of this time. By the late 1970s, predictions of future budgets and actual budgets were increasing rapidly. Then, during the Reagan years, the pressure to expand future budgets exploded, and by 1983, the projections of future budgets had totally departed from appropriations. The gross mismatch between projected and actual budgets remained for several years, before planned budgets were gradually ratcheted back in the late 1980s and early 1990s, as the Cold War ended. New readers will find additional information describing the reasons for the cost explosion of FYDPs in the Reagan Years can be found in Defense Power Games, [here] Now, consider the current situation in the context of these macro-dynamics. After a few years of decline in the 1990s, the most recent projections in Figure 8 suggest the pattern of successive FYDPs is beginning to exhibit a dynamic reminiscent of that experienced immediately after the Vietnam War - budgets are higher than predicted while growth rates for future budgets are accelerating. Moreover, the 'red' lines show clearly that the unfunded requirements in the POMs and the implications of the Senate pay and benefits vote are creating a situation that is beginning to look ominously like over-stretch of the Reagan years. Bear in mind that we now know the threat posed by the Soviet Union was dying in a morass of its own internal contradictions and corruption while the planned budgets of the FYDP were exploding of the 1980s. Bear also in mind that there is certainly nothing now on the threat horizon to cause another explosion of the FYDP in first decade of the 21st Century. So, while the macro-dynamics clearly show a system that is biased to drive up budgets over time, the bias does not appear to be driven by a rational analysis of an increasing threat. Thus, it seems safe to conclude that the quasi periodic pattern of changes and instabilities evident in the macro-dynamics of Figure 8 are powered by unbalanced internal pressures that are biased to accumulate over time before periodically going out of control. Bottom Line: The problem facing the next President is that the red lines in Figure 1 suggest the system is about to go out of control again - but on his watch. Moreover, this will happen at the same time the spending requirements for Medicare and Social Security start to mushroom as the bow wave of aging baby boomers begin to retire at the end of this decade. Bear also in mind, fully funding the 'red lines' in Figure 1 would not increase production rates enough to reverse the aging trends and, because the bookkeeping system is so unreliable, there is no guarantee that the added money will even reverse the deterioration in readiness. So even if the Pentagon gets the money, the three problems at the heart of the Death Spiral (a modernization program that can not modernized the force, a rapidly deteriorating readiness posture, and a broken accounting system) will persist and perhaps grow worse. [See Comment #169 and new readers can download the Death Spiral Briefing. Counter-Arguments: Some people might be tempted to dispute the preceding conclusions by saying I biased the argument by ignoring the effects of inflation on Figure 1. There are least three reasons for dismissing this argument as being non-substantial. First, as a practical matter, it is not possible to account for inflation in the early plans between 1963 and 1976, because the FYDPs did not include inflation predictions for the future years of entire budget. Second, inflation in military spending has little meaning in the classical economic sense. Many prices, including the estimated rates of future inflation, are set arbitrarily via bureaucratic negotiations, rather than by a competitive market. These bureaucratic effects can not be distinguished or removed from the inflation calculation. The following example illustrates one particularly egregious aspect of this general point: The FYDPs of the early 1980s assumed the high inflation rates of the late 1970s would continue well into the 1980s, but inflation dropped sharply and unexpectedly during this period. Consequently, for those annual appropriations that are spent over a multi-year period, like weapons procurement appropriations, Congress appropriated money in the early 1980s to pay for a high rates of future inflation that never occurred. While the nature of this windfall was understood in the Pentagon, the information was withheld from Congress until 1985, when the General Accounting Office blew the Pentagon's cover with audit that determined at least $37 billion in excess funds had been appropriated to cover inflation that did not occur during the three years of 1982 to 1984 [GAO/NSIAD 85-145]. But there is more. The GAO also determined that over $9 billion of the windfall was due to an arbitrary multiplier that assumed inflation in major weapons increased at a rate of 30% faster than for normal defense procurement. Once this gambit was exposed, the Pentagon stopped using the differential in its budget plans, but it continues to uses it to project inflation backward in time, in effect biasing the inflation adjustment of earlier years to make those "real" budgets and weapons costs look higher in the 50s and 60s relative to current budgets, and thus implying a larger reduction in the defense budget and lower rates of cost growth over time. So, the accounting for inflation enabled the Pentagon to reap at least $37 billion in windfall profits, much of which have never been accounted for to this day, and the Pentagon still relies on hokey inflation factors to bias the adjustment of early years. Clearly, therefore, even if it was possible to use DoD's inflation factors to remove inflation from Figure 8, the result would be misleading, if not outright disingenuous. Finally, it is important to remember that politicians appropriate defense budgets in current dollars, not inflation-adjusted dollars. Therefore, plans for future appropriations are more representative of the Pentagon's contemporaneous demand function if they are expressed in current dollars as in Figure 1. The General Accounting Office issued a report in May 1988 that illustrates one aspect of this point. According to the GAO, Secretary of Defense Cohen told the Senate Armed Services Committee on February 3, 1998, that President Clinton was allowing the Pentagon to keep the $20 billion in projected "savings" from a reduction in the estimates of future inflation and to use the money pack more defense programs into the FY 1999-2003 FYDP than were in the previous FYDP [GAO B-279943, May 11, 1998]. Conclusion Cohen's testimony also illustrates the bias to pack programs into the FYDP whenever there is any relaxation in overall budget pressure exists in the Pentagon as well as in Congress. To make matters worse, the bias to pack programs is accompanied by a bias to front load them by underestimating their future costs. The front loading bias is particularly evident in the procurement of big-ticket weapons, but it also exists in the optimistic assumptions underpinning spare parts costs, operating expenses, and savings predicted from infrastructure efficiencies and management reforms. Readers should also recall how the broken bookkeeping system makes it impossible to sort out the information needed to bring the these pressures under control [see Comment #169]. So, when (1) the bias to underestimate future costs is added to (2) the Pentagon's bias to pack new programs into the FYDP and (3) Congress's bias to add pork, and (4) it is all masked by an corrupt accounting system that makes it impossible to determine corrective action, it is easy to seen why the recurring pattern of horsehair lines in Figure 1 is really a self-inflicted wound caused by continually increasing internal pressures, punctuated by periodic bursts of sharply increased pressures. Both presidential candidates say vaguely they will provide for a strong defense. Both say vaguely they will reform social security (and by implication Medicare). By contrast, the actions of the courtiers on both sides of the Potomac are more focused - they intend to lock the new President onto the defense spending pathway indicated by the red lines of Figure 1, which are really pathways to protecting their lifestyle, not their country. My guess is that the courtiers are betting the next president won't be able to discern this latter distinction. And the current level of debate suggests they are right. Chuck Spinney [Disclaimer: In accordance with 17 U.S.C. 107, this material is distributed without profit or payment to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving this information for non-profit research and educational purposes only.] |