|

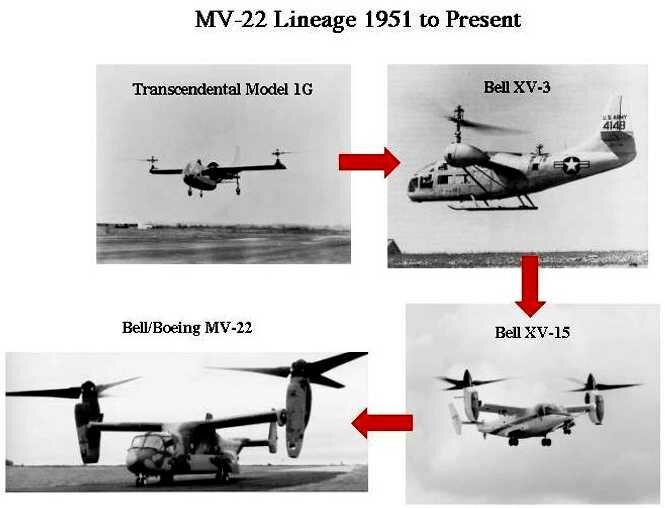

"Buy Before You Fly" & the Asymmetric Politics of Risk Reduction January 5, 2001 Comment #: 401 Embedded Reference: References: [2] Tony Capaccio (Bloomberg News), "Navy Puts Off Deal On V-22s: It wants to see a report on the aircraft's reliability," Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 6, 2000 (Attached) The MV-22 Tiltrotor transport aircraft is rapidly becoming a case study of how the factional interests of the Military - Industrial - Congressional Complex (MICC) take precedence over general interest of the taxpayers and soldiers. At the heart of this particular example, is Versailles' neo-scholastic tradition of "Buy Before You Fly." BACKGROUND The future of medium lift assault and ship-to-objective operations in the Marine Corps rests on the problem-plagued MV-22 Tiltrotor troop/cargo transport - a hybrid aircraft that is supposed to combine unique capabilities with the traditional benefits of helicopters and conventional airplanes. While tiltrotor aerodynamics is often portrayed in the popular press as being one of the Pentagon's revolutionary technologies, the MV-22 is actually an old idea that has been periodically repackaged in new clothing. Bell Aircraft and Transcendental Aircraft Company began studies for a side-by-side rotor helicopter that could tilt the rotors 90° for high speed forward flight in 1951. Because Robert Lichten, the designer at Transcendental, moved to Bell and lead their design effort in the 1950s, the MV-22 has a direct design lineage reaching back to both companies, beginning with

The pictures below show the evolution.

The MV-22 went into low-rate production four years ago in accordance with a law which allows low rate production to begin before the airplane is fully tested. In theory, production can not be increased to full rate until it demonstrates that it is ready for fleet use by passing a series of realistic operational tests known as the Operational Evaluation, or OPEVAL. The MV-22 completed OPEVAL in August 2000, and on November 17, Philip Coyle, the Pentagon's Director of Operational Test and Evaluation (DOT&E) issued a critical, heavily-caveated OPEVAL Report to Congress. Coyle identified many deficiencies and questionable waivers, but he nevertheless concluded the MV-22 was "operationally effective" if not "operationally suitable." Bear in mind, Coyle's job is not to make a recommendation for or against a full-rate production decision (another aspect of the law), but he did recommend additional testing to rectify these problems before the first operational MV-22 squadron deploys to sea - a somewhat ambiguous recommendation that could be interpreted to imply that he believed it was ok to approve the MV-22 for full rate production. John Donnelly of Defense Week has written an excellent summary of the MV-22 OPEVAL Report in Reference 1 below. The full unclassified OT&E report can be downloaded from http://www.dote.osd.mil/reports/V-22.pdf The Navy (which had been delegated responsibility for making the MV-22 production decision) reacted cautiously to Coyle's report on December 5. It announced it would defer the production decision by at least two weeks, until around December 21. Nevertheless, at that time, most people believed the Navy was simply buying a little time to figure out how to spin the story. Virtually everyone I talked to believed that four years of production had moved the MV-22 so far along that there was almost no chance that the Navy would use the Coyle Report to terminate the program and start a war with the Marine Corps. On December 5, this widely-held belief even hit the newspapers in a tragically ironic way: Bill Dane, a military aircraft analyst for Forecast International, told Tony Capaccio of Bloomberg News that "We feel that only another crash -- God forbid -- could effectively bring the program to a halt at this stage." [Ref 2] Less that one week later, on December 11, a fourth MV-22 crashed, tragically killing all four crew men. Time will tell whether Dane was correct (which I doubt), but the attitude he metaphorically revealed, with his quick dismissal of Coyle's report and his arrogant belief that nothing short of a crash would affect the MV-22's production prospects, puts a long-standing controversy in sharp relief: This is the recurring question of concurrency versus prototyping. While some readers may be tempted to regard the never-ending debate over concurrency as an obscure issue in engineering arcana, the MV-22 debacle illustrates how this debate really lies at the center of the interest-based perversion of science and engineering that has become the Madness of the MICC in Versailles. SCIENCE & ENGINEERING Few would disagree with the claim that the replacement 400 years ago of medieval scholasticism by the scientific method led to major advances in the human condition. The triumph of facts and reason over interests and faith rests on the power of a self-correcting cybernetic process that is known popularly as the scientific method. Science can be thought of as a self-correcting process of Observation - Hypothesis - Test. According to the eminent philosopher of science Karl Popper, the essence of scientific proof is testing under the Principle of Falsification. That is, an hypothesis can not be proven to be true, it can only be proven to be false by banging its predictions against the real world. Therefore, for a scientific hypothesis to have meaning, it must be constructed in such a way that it is possible to falsify it by rigorous testing. Under these logical conditions, any test that confirms an hypothesis establishes "truth" on a conditional basis only - this "truth" is always subject to further testing, elaboration, or possible falsification. The result is a gradually expanding edifice of conditional truth punctuated on rare occasions by stunning shifts in world views, known popularly as scientific revolutions. The Michelson-Moreley Experiment in the late 19th Century is perhaps the most spectacular example of punctuated epistemology in action; it falsified the Newtonian world view, which was previously accepted as being true, and helped to open the door to Einstein's new world view. Under the Principle of Falsification and the Theory of Conditional Truth, science and the evolution of knowledge can be thought of, paradoxically, as a creative search process for what does not work. Like science, Engineering is a self-correcting search process, but in this case, it can be viewed as a trial-and-error process of Observation - Design - Test. The emphasis on design gives engineering a slightly different motivating force, even though the method is the same as science. In contrast to science, Engineering can be thought of as a creative search process for "what works" in the sense of combining existing scientific principles (conditional truths) and technologies into new products that satisfy or create human needs. Engineering can be thought of as the practical application of the scientific method, where a "design" replaces a hypothesis. The principle of falsification takes the form of realistic testing of a prototype design. Once this approach determines a design that is viable in the real world, production resources can then be committed with relatively low economic or performance risk. Tests that are biased to prove success violate the self-correcting principle of falsification. In the case of science, the result is quackery. In the case of engineering, problems get suppressed and products go into production prematurely with major design flaws, with the end result being products that don't work or excessive costs to make them work. In fact, the main page of the DOT&E website http://www.dote.osd.mil/ confirms the central role that testing should have in the weapons engineering process: So, engineers use the self-correcting scientific method to evolve new and useful product designs at an acceptable cost. They do this by synthesizing and debugging a sequence of increasingly comprehensive experimental prototype designs. Engineers discover what works by a search process that fixes things that do not work. This tinkering process is not just technological; it also includes tests related to management, production economics, and market research as well as anything else that defines what works in the real world (including, perhaps, a testing of the designer's faith that a novel product will create a new market, as happened in the case of the invention of snowmobile) But classical prototyping can also be thought of as a decision-making strategy for reducing technical and economic risks while preserving management's freedom of action to terminate the effort, should testing reveal a product design to be fundamentally flawed. The decision maker's goal is to have the engineers work the bugs out of a design before a decision is made to commit substantial resources to its factors of production (manufacturing engineering, specialized machine tools, unique factory facilities, a network of supplier relationships, and the hiring of production workers). Production engineers should work closely with design engineers during a prototype's design phase to insure the final product can be produced efficiently and economically. Moreover, as more detailed information flows out of the design and testing activities, production engineers should begin planning for an orderly transition to production by continuously refining their plans for factory layouts, machine tools, worker skills, sub contractors, etc. But under a classical prototyping strategy, the decision to commit resources to production would be deferred until rigorous testing demonstrated the product met its specifications. The iron logic governing a classical engineering process is that any decision to commit more resources to an ongoing design effort must be justified by the demonstrated performance in prototype tests to date. In the end, ruthless testing of the final product in the competitive market or the battlefield will be the ultimate arbiter of success or failure - of life or death - of what really works. Prototyping can also be thought of as the engineering way of realistically preparing to meet that ultimate test. (Students of evolutionary biology will recognize immediately that this kind of tinkering and testing of prototypes is also nature's way of evolving new designs that work in the real world.) Viewed from these slightly different but overlapping perspectives, the roots the engineering process all lie in the fertile soil of the scientific method evolved by Bacon, Galileo, Newton and their successors, as well as by the natural processes in evolutionary biology. At the heart of this method is the theory of conditional truth revealed by testing and the principle of falsification. While the scientific method of searching for truth in the material world has contributed much to Western Culture over the last 400 years, the theory of conditional truth is viewed as anathema by certain primitive religious sects, fortune tellers, swamis (like Bill Dane), and the power brokers or lobbyists in the Military - Industrial - Congressional - Complex (MICC). This brings us face to face with the question of concurrency. Why does the MICC place programs like the MV-22 into production before they are completely designed and tested? Before decision makers know if the product really works? WHY REJECT THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD? The MICC's elemental animosity to the theory of conditional truth can be seen in its oft criticized practice of "concurrency." Concurrent engineering - known throughout the MICC as 'Engineering and Manufacturing Development,' or EMD, is the practice of investing in a weapon's manufacturing base and beginning its production while the weapon is still being designed. This means that the operational test and evaluation efforts, like the recently completed MV-22 OPEVAL, use weapons produced during low rate initial production (LRIP) on a working production line. By prematurely creating a working production line, the EMD/LRIP decision-making philosophy also creates a nation-wide web of technical, economic, and political connections. These connections are wedded to a particular configuration before that configuration has been fully debugged, its design stabilized, or its performance demonstrated. If operational testing reveals problems, these pre-existing connections introduce political conflicts, economic rigidities, and technical constraints that make it much more difficult and costly and time consuming to change course or iterate with a major redesign. More importantly, cancellation becomes almost impossible, because the EMD and LRIP decisions permitted the contractor to build a powerful political safety net by (1) hiring large numbers of production workers (2) building a nationwide network of subcontractors, and (3) setting up well-greased early warning net of lobbyists to ensure affected politicians know immediately when contracts or profits in home districts are threatened. Faced with these conditions, decision makers devolve into what some management theorists call "satisfycing." The normal practice in such circumstances is to simply live with the problem by (1) papering over technical flaws with band aide fixes (e.g., adding the porous wing fold fairing rather than redesigning the wing of the F/A-18E/F), or (2) reducing performance specifications to a level that meets actual performance (e.g., the repeated reduction in the range/payload requirements of the C-17, a practice known as managing to a rubber baseline), or (3) acquiescing to cost increases, quantity reductions, schedule slippages, and even testing reductions to pay for cost overruns and technical problems (e.g., F-22). While the manifold failings of EMD/LRIP have been recognized for many years, the practice continues unabated in Versailles. In fact, it is enshrined in law. In 1970, for example, the Fitzhugh Commission, a Blue Ribbon Panel established by President Nixon, recognized the problem and called for a reduction in the risks of concurrency by (1) increased use of prototypes, (2) more competition between competing designs, as well as between new designs and modifications of existing designs, and (3) a decision process adjudicated by rigorous independent operational testing prior to the production decision. Over the years, the Fitzhugh policy reforms have became known collectively by the catchy phrase "Fly Before You Buy" to distinguish it from the MICC's predilection to "Buy Before You Fly." Despite the common sense wisdom of such reform proposals, prototyping and rigorous testing before production have a long history of falling on deaf ears or, when implemented, of being de-fanged and ground into dust over time by the courtiers of Versailles. Deputy Secretary of Defense David Packard's stunningly successful fly-before-you-buy initiatives in the early 1970s are a case in point (especially the lightweight fighter program). They disappeared by the mid-1970s. The independent operational testing office (DOT&E) set up in the 1980s now presides over a legally-sanctioned operational test and evaluation process that is not complete until several years after a weapon has entered Low Rate Initial Production. Not surprisingly, once in production, political pressures for continued production encourage Orwellian evaluations of any test results that could threaten future production, like the recent report deeming the MV-22 tiltrotor to be "operationally effective but not operationally suitable." This madness raises a question: Why does the MICC insist on Buying before it Flies? THE ASYMMETRIC POLITICS OF RISK MITIGATION The answer, I think, lies in the asymmetric politics of risk mitigation and the absence of any checks and balances offset these politics. These asymmetries becomes evident when one analyzes the question of who bears the change in risk if one replaces the preferred policy of 'Buy Before your Fly' policy with the dreaded policy of 'Fly Before you Buy.' A weapons system in development faces three kinds of risks: Technical Risk, Economic Risk, and Political Risk Technical Risk is the risk that a weapon will not work as well as expected or specified. The ultimate bearers of this risk are the soldiers who will have to use this weapon in a future war. Economic Risk is the risk that a weapon system will cost more to buy or operate than was originally predicted when the program was approved. This risk is born ultimately by the taxpayers who foot the bill. Political Risk is the risk that a weapon system program is cancelled or terminated for any reason. This risk is born primarily by the Faction that is responsible for and benefits from the program's continued existence. This faction is made up of (1) the people in the Defense Department whose future promotions and status are tied to the program's continued funding (in the program offices, support staffs, etc.), (2) the network of contractors who receive the money and build the system, (3) the politicians whose districts receive economic benefits of the money flows to the contractors (dollars, jobs, profits), and (4) a variety of hangers on, including lobbyists, journalists, and academics who are associated for one reason or another with the success of the program. The first point to note is that the different risks are borne by different groups. The second point to note is that concurrency and prototyping policies affect these risks in very different ways. The early establishment of the political safety net means that concurrent 'Buy-Before-You-Fly' policies' reduce political risks to Faction. But this increases the economic and technical risks to the taxpayers and soldiers. On the other hand, 'Fly-Before-You-Buy' prototyping policies reduce technical and economic risks by highlighting problems earlier and making it easier to cancel a program, should it not perform as expected, but that flexibility increases the increased political risk to the Faction that benefits from the programs continued existence. The third point to note is that the acquisition community in the Pentagon, which represents the interests of the faction, selects the overall policies that determine what risk tradeoffs are actually made. Put another way the faction - the MICC -- has the power to manage its own risk. It should not be surprising, therefore, that the MICC shapes engineering policies (and supporting laws) to reduce political risk while accepting increased economic and technical risks. After all, the MICC is spends other people's money and risks other people's blood. During times of peace, the risks of benefiting the Faction at the expense of the general welfare may seem modest and disconnected because these risks are either diffuse (in the case of taxpayers) or hidden in the mists of the unknowable future (the risk to the soldiers fighting in an undefined future war). But these risks are not inconsequential over the long term. The following article about the MV-22 illustrates how this asymmetrical pattern of risk can unfold in the real world. It is written by my good friend J. Stryker Meyer, AKA Tilt Meyer. Tilt Meyer (no relation to Tilt Rotor) is a former green beret with two combat tours and a purple heart from Vietnam (working out of MACV-SOG for you spook aficionados). He describes the consequences of this kind of tradeoff for the case of the MV-22. Tilt writes with passion and anger. But remember, he was a soldier in the meat grinder, and is now a taxpayer to boot. So don't let that distract you, I have checked this analysis out with and have been assured that he is saying what others believe. Osprey Is a Disaster Waiting To Happen The two fatal crashes of the MV-22 tilt-rotor aircraft this year, which killed 23 Marines, have revealed flaws in the military-civilian testing and purchasing of new military hardware which must be addressed by an independent counsel or congressional hearing headed by Vice President-elect Dick Cheney. When Cheney was secretary of defense under President Bush, he tried to kill the MV-22 program. He lost the fight to a Congress that spread MV-22-related contracts across more than 40 states, pouring millions of dollars into their districts, instead of seeking out a new, reliable aircraft for the Marine Corps. But the deaths of 23 Marines demand an objective probe into what went wrong, a probe beyond the politicized gung-ho aviation Marines and Navy air personnel, which includes honest critics of the MV-22. Such an investigation would reveal that the system is inherently flawed and incapable of objective analysis of new military equipment ---- or, more gravely, that there has been a conspiracy to hide the MV-22's flaws. For example, after the MV-22 crashed in Marana, Ariz., killing 19 Marines in April, it was revealed that there was little or no training for pilots in a phenomenon called "power settling," or asymmetrical vortex ring state. The MV-22 can fly like a plane, or rotate its huge propellers upward, to fly in a helicopter mode. Power settling can occur while in the helicopter mode. Marine brass reluctantly admitted that during the mandatory 65 hours of training on flight simulators, pilots received no power settling training. Helicopter pilots are trained in that phenomenon. Marine brass laid blame for the crash at the pilots' feet, saying they exceeded the recommended rate of descent for the MV-22, which is 800 feet minute. Yet neither Marine nor Navy aviation officials will produce any flight instruction manual for the MV-22 which shows that rate of descent was in place when the MV-22 entered into power settling, where the right propellers in effect stalled while the left side pulled up, rotated the aircraft's nose around and plowed into the ground, killing 19 Marines. Another helicopter phenomenon that MV-22 pilots were not trained for is autorotation. That occurs when a helicopter loses its engine or power while in flight. If the helicopter has enough forward air speed, the chopper's blades go into autorotation, allowing the aircraft to descend for a rough landing, but a landing from which the flight crew and passengers can walk away. One Pentagon insider has said that sometime in recent years, a chief of naval operations waived that training. Why? When airplanes lose power, they can glide. When helicopters lose power, they autorotate. Both require training. Yet none was conducted for the MV-22. If this trend continues, such an oversight will impede the aircraft's marketability in the civilian market, as the FAA has stringent standards for rotor aircraft meeting autorotation standards. Additionally, during the operational evaluation, there were many times that training flights were canceled when the MV-22 landing zone was in open, unpaved areas. They were canceled due to the excessive amount of prop wash generated by the huge propellers. It appears that the Navy and Marine aviation brass who are pushing for this aircraft had so much confidence in it they were willing to forgo training in power settling and autorotation. If a probe is conducted, it will have to focus on a system where the lead pilot during what the military calls operational evaluation ---- which was ongoing during the Marana crash ---- was scheduled to become the lead pilot of planned first squadron of MV-22s. The pilot killed in the Dec. 11 crash had defended the MV-22 during closed-door meetings when military brass reviewed the final operational evaluation. How objective can the future commander of a squadron be during operational evaluations? Recent media reports state the cause of that crash may have been some sort of hydraulic failure. Again, some critics have said the MV-22 is a maintenance nightmare. Yet such criticism receives little public notice. I've talked to MV-22 crew members who acknowledged that the plane requires a lot of maintenance, but they would not go into detail about how serious that problem is. If a new aircraft requires high levels of maintenance, what will happen after it's become the lead aircraft for the Marine Corps, which wants to purchase 360 of these birds at a cost of $40 million to $80 million each? How often will the fleet be shut down for maintenance? When Uncle Sam's Marines get called to action they need sturdy, reliable, dependable aircraft to get them into the target and return them to the base of operations, be it the terra firma of the United States, or a Navy ship. Last, but not least, the probe must examine why the Marines are blindly marching in lockstep in support of the MV-22. I've met and interviewed the commandant of the Marine Corps, James Jones. I know he would never jeopardize any Marine's safety. During the summer, Jones extolled the virtues of the MV-22, saying it could revolutionize civilian air traffic and transport around congested cities in the United States. Yet the internal system of checks and balances for testing and evaluating have failed Gen. Jones and the Marine Corps. There are critics, within and outside the Pentagon. Yet those voices have been stifled in the reports and evaluations submitted to Gen. Jones. The Blue Ribbon Commission, recently created by Secretary of Defense William Cohen to study the recent crash, has no critics on it. It will be one more rubber stamp that will support the MV-22 program without putting the aircraft and the system under the microscope. GAO investigators have gathered information on the MV-22 which one critic calls "damning." But when will the GAO report be concluded? Will any of that information be shared with the commission? Will the public ever know the truth about this aircraft ---- the public whose taxes will be used to buy it? I doubt it. During the summer, Gen. Jones and his wife flew in the public return of the MV-22 to flight status after the tragic crash in Arizona. I flew in the MV-22 next to the aircraft that carried the Joneses. That flight was impressive; the power of the aircraft was felt by all passengers. The Marines need a new, tough aircraft. Critics say the MV-22 isn't tough enough or reliable enough. Aviators say the flight manual for new aircraft is written in blood ---- the blood of test pilots and test crews. The MV-22 flight manual has the blood of 14 Camp Pendleton Marines in it -- ground-pounding, hard-training, pride-of-the-Corps Marines. Before one more combat troop flies on the MV-22, which I call the Killer Albatross, the aircraft and the system that has forced it down the military's throat must be examined. J. Stryker Meyer is a North County Times staff writer. -----[End of Tilt Meyer's Commentary]---- Tilt Meyer is writing about a specific triumph of special interests over the general interest. His solution is to impose draconian checks and balances into the MV-22 controversy, which is probably justified under the circumstances. But fixing the MV-22 won't fix the larger system. All weapons acquisition is based on concurrency that authorizes the kind of buy before fly solutions that can lead to the kinds of problems described above. The larger problem is to control of the factional interests represented by MICC. Implementing an iron-willed policy of "Fly Before Buy" makes more than engineering common sense, however. A true Fly Before Buy policy, based on the ideas of conditional truth and falsification, would foster a self-correcting atmosphere of scientific integrity that would reduce the extraordinary need for the checks and balances described by Tilt Meyer. Finally, Fly Before Buy policies would a would introduce a system of checks and balances to protect the general interest from factional interests, and in this sense, would reflect a return to constitutional common sense (see Federalist #10). [Disclaimer: In accordance with 17 U.S.C. 107, this material is distributed without profit or payment to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving this information for non-profit research and educational purposes only.] BY JOHN M. DONNELLY AND CHRISTIAN LOWE The Marine Corps new tiltrotor aircraft, the MV-22 Osprey, only passed its operational tests because "significant" requirements were waived, and it has proven so unreliable that it may become an "unacceptable burden" on the rest of the fleet, the Defense Department's top tester says. Pentagon Director of Operational Test and Evaluation Philip Coyle, in a Nov. 17 report to Congress obtained by Defense Week, concludes the MV-22 is not "operationally suitable." He grades it "operationally effective" but adds numerous caveats. The MV-22 takes off and lands like a helicopter, yet flies like an airplane. So far, three of the tiltrotors have crashed, including one in the Arizona desert in April, killing all 19 aboard. Coyle says the "vortex ring state" phenomenon that doomed that aircraft is still not fully understood, and MV-22 pilots may still have little warning before they could plunge into an irreversible descent (See related article) News of the testers' concerns comes less than a week ahead of a scheduled Dec. 5 Navy meeting to authorize full-rate production of 360 MV-22s by Textron's Bell Helicopter and Boeing--a $30 billion decision. Another 98 tiltrotors will be built for the Air Force and special-operations forces, a separate production decision that comes in 2002. The total acquisition cost for the 458 aircraft is $40 billion, one of the Pentagon's biggest bills. Coyle's decidedly mixed review is unlikely to sidetrack the top-dollar program. However, while all aircraft programs have difficulties, the MV-22 looks like it will require considerable additional testing and vigilant attention to maintenance concerns to ensure it performs its missions without breaking the Pentagon's bank. After being killed by Republican vice presidential candidate Dick Cheney's Pentagon in 1989, the MV-22 was resurrected by Congress in 1994. It is intended to take Marines to combat zones far inland from ships located over the horizon at sea. It also should do non-combatant evacuations, hostage rescues and recovering downed pilots. It will replace the Marine Corps' CH- 46E Sea Knight and CH-53D Sea Stallion. Distinct advantages' "I think that we are impressed and gratified at the detail-conscious and articulate and precise manner that Phil Coyle has reported," said Doug Kinneard, a spokesman for the contractors. "It's what's going to help make this as good an aircraft as it's going to be when it's flown in combat and when it's saving lives. ..." Marine Corps 1st Lt. David Nevers, a spokesman, said the aircraft is ready for full-rate production. The problems identified by Coyle have "either been addressed or there's a plan in place to address them," he said. Coyle's assessment contained praise for the aircraft. Its speed, range, payload and survivability characteristics offer "distinct advantages" over today's helicopters and "a major step ahead in tactical flexibility," he said. In its "operational evaluation" tests, the MV-22 proved it could cruise at 267 knots, carry 24 troops and a 10,000 pound external load, and fly a maximum unrefueled radius of 265 miles. The Coyle report summarizes the results of these tests, in which four MV-22s from the first low-rate-production lot flew 800 flight hours at various locations, including from the decks of amphibious assault ships at sea. However, there aren't yet enough MV-22s to simulate what might happen when 24 MV-22s--the number required for a major amphibious operation from ships--must be transferred from hangar to flight deck, and be refueled, loaded, recovered, recycled, etc. More of this "end-to-end" operational testing is needed, Coyle said. Suitability As configured and tested during the evaluations, "the MV-22 was not operationally suitable, based primarily on reliability, maintainability, availability, and interoperability issues," Coyle said. "Whereas the objective is for the MV-22 to reduce the current maintenance burden associated with medium-lift aircraft, these deficiencies, if not corrected, will make the MV-22 more difficult and costly to sustain than the current fleet," he said. While the MV-22 will probably be able to perform most of its missions, Coyle's report brings its cost effectiveness into question as the Pentagon considers a bill worth several hundred billion dollars for three new tactical fighters. Moreover, the MV-22's potential for runaway operating costs runs counter to the Pentagon's recent emphasis on cutting "life cycle costs," the 20-year costs to not just buy but also operate and maintain weapons. In several key measurements of suitability--including mean flight hours between abort, mission reliability, mean time between failure, mission capable rates, maintenance man-hours per flight hour--the MV-22 compares unfavorably with the CH-46 it is replacing, Coyle said. Moreover, to the extent that the mean time between failure is "marginally" better than the CH-46, the report found, it is at the cost of greater (70 percent above requirements) maintenance man-hours and reduced mission capable rates. The high failure rates could put more stress on a military aviation network whose readiness is already stretched thin. The failures "portend high demands on spares that are chronically underfunded and maintenance man- hours resulting in increased costs, overworked maintainers and poor aircraft availability," Coyle said. "Comparison with fleet data from the CH-46 indicates that the MV-22 as tested in (the operational evaluation), poses a greater maintenance burden than does the very old aircraft," he said of the CH-46, which averages 30-plus years. "Unless corrected, these suitability shortfalls will impose an unacceptable burden (cost, manpower, mission reliability and operational availability) on the operational fleet." In addition, the minimum requirement for mean time between aborted missions is 17 hours, but the MV-22 had to abort every 13.9 hours during the tests, the report said. Effectiveness issues A major asterisk to the Coyle's rating of "operationally effective" is his note that the Chief of Naval Operations waived numerous requirements. The reasons for the waivers included incomplete testing of subsystems or the need to redesign them. In the case of a defensive gun, the money to pay for it hadn't materialized. As a result of Navy waivers, the report said, the following "significant" shortfalls exist: "aircraft flight envelope not cleared for air combat maneuvering; no flight allowed in deicing conditions; inadequate nuclear, biological and chemical overpressure protection; inadequate cargo handling system and airdrop capability; unable to carry external loads at night due to incorrect radar altimeter readings; no production representative auxiliary fuel tank; unable to fastrope out of the cabin door." The Marine Corps' Nevers said the deficiencies were "not crucial to the operational effectiveness and suitability of the aircraft," and the MV-22 has "met or exceeded its key performance parameters." In fact, he said, the number of waived requirements that the MV-22 program asked for and received was "the lowest of any aircraft in aviation history." While Coyle acknowledged that the V-22 program office has come up with plans to correct these deficiencies, they still need to be independently tested, he said. Downwash Another major issue is the MV-22's "downwash"--a strong blast from its powerful rotors and exhaust that can inhibit the safety and effectiveness of personnel operating under them. The glitch has vexed the program for years. Coyle credits officials with making progress in working around the problem-- such as having personnel approach the aircraft only from certain directions. But the work-arounds don't eliminate the problem. "Nonetheless," Coyle said, "testing has demonstrated that some required capabilities (e.g., landing at night in desert environment) can be conducted only with great difficulty, some (required) capabilities (e.g., use of a rope ladder or three simultaneous fastropers) are unlikely to be achieved, and some planned capabilities have yet to be tested for downwash effects (e.g., personnel rescue from sea)." These are the very missions for which the special-operations and rescue forces say they need the MV-22. As for survivability, the aircraft's range and speed will keep it alive in many scenarios, Coyle said, but the aircraft doesn't carry enough chaff and flares to counter threats that are guided by radar or infrared seekers in a "typical threat scenario." During numerous missions, the MV-22 shot all of its load of chaff and flares entering combat areas, and none were left for exiting the area, he said. In addition, the aircraft's automatic diagnostic equipment was mostly "ignored" by the crews, he said: "Indeed, since the vast majority of fault detections were invalid; i.e., false alarms, the diagnostic system overall was of little, if any, assistance to the operation or maintenance of the aircraft." Finally, the MV-22 got bad marks for "interoperability" with other combat units and battle-management systems because "communications remained the one area where the MV-22 was most deficient." It didn't meet requirements for Ultra High Frequency satellite communications, anti-jam capabilities and more, he said. Pilots Need Warning Of Deadly "Vortex' A physical phenomenon that caused 19 Marines on board an MV-22 Osprey tiltrotor aircraft to drop to their deaths last April can still overcome pilots without warning, the Pentagon's top tester says. Yet changing the way the tiltrotor is flown to avoid the vortex's onset can hamper the warplane's effectiveness. An April crash of an MV-22 at Marine Corps Air Station in Yuma, Ariz., was due, the Marine Corps says, to "human factors." In other words, the MV-22 pilots flew outside the "envelope" in which the tiltrotor can safely fly without encountering a "vortex ring state." The vortex occurs when the aircraft descends too rapidly at too low a speed. When that happens, the rotors that keep the Osprey aloft can't provide enough lift and the tiltrotor's descent can't be corrected by increasing power. The phenomenon is common to all rotorcraft aircraft. But Coyle thinks the V- 22 should have some system to warn pilots when they're approaching the conditions that lead to vortex ring state. He said "there may be no easily recognizable warning that the aircraft is nearing the danger zone. ... Such a situation can easily be envisioned in flight conditions that place a high workload demand on the pilots; e.g., night or low visibility, system malfunctions, hostile fire, etc., should a breakdown of crew coordination or loss of situational awareness occur. Thus, the first indication the pilot may receive that he has encountered this difficulty is when the aircraft initiates an uncommanded, uncontrollable roll." Coyle urged further testing of this problem with the aim of giving pilots some warning when they might approach the danger zone, via cockpit instrumentation or other means, and sufficient training to avoid the situation. The solution the Marine Corps has picked to date may cause problems of its own, Coyle warned. Since the April crash, MV-22 pilots are proscribed from descending more than 800 feet per minute at airspeeds less than 40 knots and nacelle angles greater than 80 degrees. But those restrictions may hamper the MV-22's agility. Coyle said "this constraint, imposed to avoid loss of control, may limit the maneuver capability and hence the effectiveness of the MV-22 in some operational scenarios." The Naval Air Systems Command plans further study of the issue. Until the answers are in, however, "the potential impact on the effectiveness of the MV-22 in performing some combat assault missions must be viewed with some reservations," Coyle said. --John M. Donnelly and Christian Lowe Fort Worth Star-Telegram Navy Puts Off Deal On V-22s It wants to see a report on the aircraft's reliability By Tony Capaccio, Bloomberg News Excerpts: WASHINGTON -- ... The initial full-production contract to be signed in March would be for 16 aircraft, followed by 19 Ospreys in 2002 and 28 in 2003. Bell would handle final assembly of the aircraft at its Amarillo plant and make parts in Tarrant County. About a third of Bell's 6,400 workers in Fort Worth and Arlington are engaged in V-22-related work. ... Although it has demonstrated that it can perform its primary combat missions, the Osprey proved so unreliable during 800 hours of combat testing that many maintenance problems would probably arise during combat missions, Coyle's report concluded. In tests, the V-22 had a worse reliability record than the helicopter it's replacing, which is 36 years old, Coyle wrote. "Unless corrected, these issues will impose an unacceptable burden -- cost, manpower, mission reliability and operational availability -- on the fleet," Coyle wrote. ... Despite the government's delay, the Navy is still highly likely to give the go-ahead for full production because "the Marines desperately need it," said Bill Dane, a military aircraft analyst for Forecast International, a defense marketing firm based in Newtown, Conn. "We feel that only another crash -- God forbid -- could effectively bring the program to a halt at this stage," Dane said. "It's our take that the Navy and Marines will fine-tune V-22 improvement. We don't expect this report to result in any more than a six-month slip in deliveries." A Marine V-22 crashed April 8 while trying to land at an airfield near Tucson, Ariz., killing 19 Marines. The crash was attributed to human error. |