|

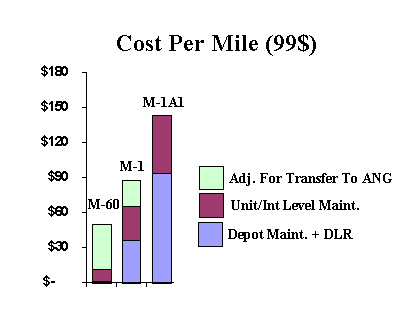

A Strategic Question for the Grand Strategic Dice Rollers ... or ... February 20, 2003 Comment: #475 Discussion Threads - Comment #s: #348: Why Syncronization Dumbs Down Your Ooda Loop #372 - Sayen Report: Officer Bloat Creates the Shortage of Captains Attached References: [Ref. 1] David Wood, "A Cautionary Tale In The British Invasion Of Iraq," Newhouse News Service, January 15, 2003 [Ref. 2] "Is water Saddam's secret weapon? Dictator could blow up dams near Baghdad to flood U.S. troops," WorldNetDaily, February 19, 2003 Question? There is a general consensus that a war to topple Saddam Hussein will be over quickly, and most of the concern relates to dealing with post-Saddam Iraq. Most observers also agree that a quick clean victory is a necessary grand-strategic condition for keeping rising popular tensions to a manageable level in the neighboring Moslem countries like Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Pakistan, etc. Most observers would also probably agree that all bets are off if the war gets drawn out, and images dead Iraqi civilians and destitute Iraqi refugees start flooding the airwaves of CNN and Al Jazeera. So, the strategic question for the grand-strategic dice rollers is: Will we win this war quickly? Introduction No one can answer this question, least of all a civilian like myself. But as citizens of a country that is becoming progressively isolated in the world, we all have a moral obligation to make ourselves better informed about some of the conditions which might shape that answer. It is clear from the publicly announced deployments that the main weight of an operational maneuver into Iraq will come from bases in Kuwait to the south, with lesser weight thrusts being possibilities from the north out of Turkey or the Kurdish regions of Iraq, and perhaps even from the west out of Jordan. We are told by reporters that these ground attacks are likely to be preceded by a short "surgical" air campaign aimed at isolating Saddam's forces and decapitating the government from people without destroying the national infrastructure or killing or making refugees out of large numbers of ordinary Iraqis. But at the end of the day, we must remember that Baghdad is a long way from Kuwait, and Saddam certainly knows that sooner of later our heavy Armored units will have to leave the hard desert and cross the Euphrates River and move into the soft ground Mesopotamia (the densely populated, fertile region of dikes, dams, and irrigation ditches between the Tigress and the Euphrates). What many of our all-knowing pundits do not remember is that this operation will not be the first time a modern western army marched through Mesopotamia toward Baghdad from the south. In Reference 1 below, David Wood of Newhouse News, on the finest reporters now covering the defense beat, reminds us of the now almost forgotten British Mesopotamian campaign in 1915 of 1916. The Brits were supremely confident of their military superiority over the decrepit Ottoman Army, and believed they could secure the country's oil, capture Baghdad, and bring about what would be today called a quick regime change. What happened was, according to Wood, a "sobering lesson for imperial ambitions in the place now called Iraq." The campaign turned out to be a" colossal and costly blunder, a bloody, nightmarish tragedy of incompetence, slaughter and betrayal." His report is reproduced in its entirety as Ref 1 below -- I urge you to read it carefully. No one doubts that the troops of the US Army are far better prepared for this fight than were their British forbearers, but Baghdad is still a long way from Kuwait, and Mesopotamia is still a swamp waiting to happen. Reference 2 below suggests that Saddam is fully aware of the potential for stretching out the war with a flooding strategy converts this part of the Fertile Crescent into a muddy quagmire. I urge you to read it also. Now, armed with these somewhat sobering views, let us proceed to the meat of this blaster. Discussion A few days ago, I received an email from one of our subscribers asking me if I knew anything about the logistics problems that must be overcome in the looming war with Iraq. My correspondent, who is a pro-military patriot, was worried, because he remembered a conversation he had with an Army colonel in 1991, shortly after the completion of the ground campaign in first war with Iraq (Operation Desert Storm). That colonel -- a logistician by training -- told my friend that the logistics requirements for keeping the M-1 tanks moving across the hard desert had grown exponentially with time. The colonel also alleged that former Secretary of Defense Wienberger had warned then Secretary of Defense Cheney and General Powell that the ground campaign could not continue beyond seven days for M-1 tanks and ten days for M-2 Bradley Fighting Vehicles before these requirements bogged the operational maneuver down. At the end of two weeks, according to this colonel, the only thing that would still be moving would be the Paladins (i.e., the M-109 self-propelled artillery pieces). This was all my correspondent knew, and I want to stress that he acknowledged that the colonel's story may well be apocryphal, but my friend wondered if the newer versions of the M-1 tank -- the M-1A2SEP -- had reduced the logistics burden. I do not know much about Army logistics, but I do know that M-1A2SEP significantly increased the electronic complexity of the M-1 tank over the preceding model -- i.e., M-1A1 (these changes are explained in Endnote #1). Moreover, as the as the chart below shows, the operating cost per mile has increased dramatically as more modern tanks have replaced older tanks, which is at least superficially consistent with the colonel's assessment.

These operating costs are a partial reflection of the logistics burden, but they are not the whole story. The first point to note is the chart does not include data for the M1A2 SEP, but as Endnote 1 shows, the M-1A2SEP has even more complex electronics than the M-1A1, so its operating costs are likely to be even higher. Note also that the prime driver in the growth of operating costs is the growth in Depot Maintenance and DLRs (which stands for Depot Level Repairables). DLRs are primarily the "remove and replace" black boxes that must be checked out on computerized test equipment in the intermediate level maintenance shop (usually at division level) to identify the broken parts, before they are shipped back to the distant depot for repairs. The only way to effect a repair of broken DLRs in the field is to replace them, so the logisticians, like the aforementioned Army colonel, must able to identify and carry a sufficient quantity of high cost spare parts with them to effect the field swap outs required for the duration the planned operational maneuver. These parts must accompany the tanks all the way to Baghdad. But this is still only a superficial first cut into at the logistics problem -- and from here on, I am way out of my depth. So I asked my friend Officer XXX what he thought about the combat logistics question. XXX has experience in armored operations. What I received stunned me. I believe he has written a very important and, I think, sobering discourse at the logistics burden of a modern American heavy division. Officer XXX also explains why he worried that a disconnect at the operational level of war could decapitate our strategy from our tactics. If you have any interest in understanding this nuanced point, I urge to read his tutorial on the role of combat logistics from an operational or grand tactical perspective. ----------[Officer XXX's Response]------------ A Short Tutorial on Combat Logistics from an Operational Point of View By Officer XXX February 18, 2003 What your friend says could be true, but lets look at it from the Army's prospective, which ignores the larger levels of war. I have served on three types of tanks, the M48A5, the M60A3TTS (tank thermal sight), and the M1A1 heavy (additional armor). I have never dealt with the latest version of the M-1 tank, the M1A2 SEP [but it is described in Endnote 1], which has many electronics enhancements, most importantly the Independent Thermal Viewer which allow the Tank Commander to scan and lock in on targets while the gunner is fighting. Nevertheless, I can imagine it is about the same as the M1A1 heavy, except with more electronics to worry about. The increased logistics of the M-1A2 really does not matter in the coming however. There is only one battalion in the Army with M1A2s, so any impact will be minimal in the grand scheme of things. Bear in mind, I have not been on tanks in the field for a little over five year, nevertheless, I have kept abreast with what armor/heavy units are doing. With regard to my experience in armor, suffice to say I have been on several major exercises such as Team Spirit in Korea (Grand tactical and Operational levels of war), as well as over 50 rotations at the two major training centers for our heavy force -- the NTC in California, and CMTC in Southern Germany (tactical level). It is important to focus on how the Army trains to get insight into what may impact its conduct in Gulf War II. Lets begin at the tactical level of war: The Army mentality is stuck at the tactical level of war, and this runs all the way up through the top ranks because it is product of our culture of micromanagement, which translates into "the obsession with Attention to Detail in trivial matters." Lets start with the tank crew. The U.S. trains its tank crews and platoons well. We still have the best trained crews in the world, notwithstanding the 50% decline in opportunities over the last 10 years, as documented by studies by the RAND Corporation and the General Accounting Office (GAO). I would like to know what the training of the Republican Guard is and what their standards are? I am sure it does not compare well to ours. While our training is good, teamwork is undermined by the individual replacement system. I found out through a top-level contact at the Army level and a first sergeant that just left the division in the summer of 02, just as 3rd Infantry Division was pulling out for Kuwait, and the division was still changing over crews (to account for soldiers who could and could not deploy for a myriad of reasons). Now, what can the crew can do to keep the M1 moving? While what your friend says is true, it is not the whole story. If a tank crew is motivated, and the company/battalion maintenance crew is good i.e., they "walk" and maintain their track for an hour for each hour of running; they keep the air filters clean, and they keep up with the lubrication levels, and if this crew has available 10/20 level (crew and direct maintenance level support) supplies, then the M1 is a solid tank. Or as I say, it is great, as long as we fight in our back yard. As one friend told me years ago -- the M-1 is the worlds fastest strategically immobile tank. I remember going through a 10 day rotation at CMTC or Combat Maneuver Training Center (I went through two at Germany as a company/team commander) and 14 days at NTC or National Training Center (one as "Blufor" in California as assistant to the brigade commander (36 as "OC" and 16 as "OPFOR")) respectively, and M1s were maintained at 75-85% percent strength. In some fights I would have 100 percent strength for my company which was 14 tanks. Bear in mindsome maintenance issues necessary for a real battle can be ignored on the MILES battlefield, for example, some parts of the tank's precision fire control system. (MILES stands for Multiple Integrated Laser Engagement System -- it is a scoring system to grade simulated tank fires.) But, remember, the Army is focused on -- indeed, it is mentally stuck in -- the tactical side of war. Leaders are obsessed with synchronizing the operating systems! Look at how the Styrker brigades have been tested/evaluated -- the vehicle is designed for operational level maneuvers, yet the test/evaluation program did not include any operational level long distance road marches! But the real answer to your question lies at the Grand tactical and Operational level of war (or what is ignored in my Army's culture): No battle at CMTC is more than 30 Kilometers distance from assembly area to objective. The only long road march is from the railroad download area to CMTC, maybe 50 kilometers. At NTC, of course the size of Rhode Island, you may do a major offensive fight every third day for at the most 100 kilometers. These limited distance and the de-emphasis of operation maneuver in training has a profound impact on our perception of logistics requirements. While operations maneuver is "played at" in both training centers, real operations do not stress the maneuver force beyond the tactical fight. Missions end at the "objective" and do not go forward once the objective is achieved. The objective is usually defined as a geographic point 30 to 50 kilometers from the "LD" or line of departure, on the mind of our adversary's OODA loop. BLUFOR forces (the good guys) as well as the OPFOR forces (the bad guys) can "rekey" after the objective is met, and in the sense of maintenance, they get a breather to "fix" what is "broke" for the next battle. And that tactical context determines what commanders up to the brigade level ask their XOs and maintenance officers, question like "how many tanks and bradleys are up?" The observer controllers also brief this maintenance measure on their AAR (After Action Review) slides. So, the training focus of maintenance is on giving leaders up to brigade (at NTC) and the task force (at CMTC) authorized levels of vehicles and personnel so they can train at the tactical level -- not supporting units who are executing a deep operational maneuver. Lets look at the logistics training in this context. The logistics supply line runs from where ever the battalion is on the reservation back through the task force Field Trains, 15-30 kilometers, then on to the brigade Forward Support Battalion (FSB) --a brigade asset which consists of a supply, transportation and maintenance companies, then along a road back to "mainside" or "post" where supplies are procured for a return trip back. At the training centers, ammunition is replicated, except when the units do the live fire phase at NTC. If this were a true supply line, in theory this would run another 50 kilometers to a DSA or Division Support Area, then another 50-100 kilometers to a CSA or Corps Support Area. But in reality, the supply line does not stress/stretch that far. At the most, from the tank back to the source of supplies, at the NTC is maybe 150 kilometers if it is stretching along East Range Road up through Red Pass to supply the brigade (-) at Live Fire in the north; at CMTC it is at the most 30-50 kilometers. Additionally, everyone knows "in 10 days it is done," so you can stay motivated, and keep up your strength. Logistical work is thankless, but backbreaking. Tactical or HEMMIT fueling trucks have to refuel from larger division assets who are traveling to and from resupply points 24 hours a day. Each M1A1 Team (company) needs two HEMMIT fuelers with the 10 tanks in the team burning three gallons per mile. This translates into two refuels from the HEMMITs per day for all the vehicles. Remember, those refueling trucks have to turn around and link up with larger fuelers. We are not even accounting for the rest and maintenance of the trucks. The truckers (guys and gals) have to pull on themselves and their vehicles, and the burden will get worse as the campaign continues and wear and tear and distance increase. There is also ammunition that must flow into moving units that are expending it at a very high rate. Given the U.S. emphasis on attrition and firepower, the ammunition requirement translates into thousands of various types of transports from HUMMER trailers through 5-Ton trucks, to HEMMT trucks to larger flat bed trucks at the division level. These truckers are always on the move, especially if we practice the same "Methodical battle" approach we preformed in Gulf War I, because whenever contact was made, maneuver units stopped, brought up artillery and smothered the enemy with supporting fires. And the M1A1, despite its precision fire, burns up a lot of ammunition in a fight. Again, the focus in training is ensuring the enemy is blown to pieces before occupying the objective. In addition, everyone will be nervous and will expend more ammunition to reassure themselves that the enemy is killed. Thus, a lot of ammunition from main guns and machine guns, as well as what is being fired by indirect artillery, will be expended to ensure the enemy is taken out. Suppression in order to enhance maneuver is great at NTC, but it almost does not exist on the real U.S. battlefield as was seen during Gulf War I. Basically, it was line our forces up, out range them and kill the enemy, then move, if your allowed to move by the higher officers. In exercizes, this also means those soldiers that serve in Division and Corps support units don't get stressed that often, if at all, in a combat like environment. Additionally, it is important to remember that supply lines at the training centers were not subject to raids, or interdiction by opposing forces. The OPFOR (the bad guys) runs reconnaissance back to the brigade rear area, but they are not allowed destroy fuelers in order to stop tanks. They are not allowed to take out ammo convoys as well. A competent officer with lots of troop time, as well as academic time, brought up a good point point to me in this regard. In Gulf War I we deployed additional units, from divisions not employed, to guard the rear area, to free supports units from worrying about their own security. That is when the Army had 780,00 active duty soldiers. Oh by the way ... there is gunnery training as well: Tank and Bradley units do gunnery at fixed ranges where target arrays are known to all. There is no "chance contact" gunnery. Crews focus on drill and scripted fire commands. Crews, with their officers over watching stand endless hours watching other tanks making their "runs" down the gunner course, so they know where every target is, "they G2 the course and know how to play the game" The goal of this kabuki dance, of course, is to brief the highest gunnery scores at quarterly training briefs. I made a proposal a couple of times that the computer generated ranges should present different target arrays to each tank as it began its run to test its decision making skills. I was voted down because it was seen as unsafe, and would lower scores relative to the other battalions and companies, thus adversely impacting our Officer Efficiency Reports. By the way, that is how it goes if a battalion, Tank or Bradley unit does a "full up" gunnery excercize. I know a First Sergeant of a tank company that told me they now do "mini-gunnerys" in order to get lieutenants some experience in "fighting their tank" before they are rotated out every six to nine months. This mini-gunnery also saves money. Gunnery, behind the baseline: On the maintenance side, this kind of gunnery training is not so taxing. Tank crews shot every other day. After they shot, they get an after action report (AAR), then do crew maintenance and rest and prepare for the night shot and then skip a day to prepare for the next higher gunnery range. In between, battalion maintenance works non-stop to keep tanks up and going. Most of the maintenance problems are with the fire control systems. This includes the thermal night sight, the ballistic computer, and etc...If the part is available, a good maintenance crew can have the tank going again in a few hours, but they can not repair most breaks in the field. Units that are going through gunnery are also "plussed" up with extra supplies. Meaning that they are given priority in the division for critical parts, such as thermal sights and ballistic computers, as well as engines and transmissions. These items are expensive, and are not stocked in great numbers, so it is natural for division and brigade commanders to take their limited budgets and give priorities to those who are training. What does this all mean: So in sum, you have a system where everyone can line up to fight for 12-24 hours (including the reconnaissance/counter reconnaissance fight), then pause for what is called "prep phase" for the next battle 24 hours away. As this goes on there is no real threat to the logistics supply line. Gunnery training is the same pattern. As a result, the grand tactical and operational art of war is not stressed during "peacetime" training. Day 3 of Gulf War I is a case in point: units were running out of fuel, and slowing down the tempo (which was already made too slow by methodical attrition doctrine) in order for supplies to keep up. That supply line was only around 150-200 kilometers -- the distance from Kuwait to Baghdad is much further. So, I am concerned about the distance our forces must cover, and that concern relates to the grand tactical and operational level of war, but it is something we don't really train for in the U.S. Army. Endnotes [1] M1A2 System Enhancement Package (SEP) -- In February 2001, General Dynamics Land Systems Division (GDLS) were contracted to supply 240 M1A2 tanks with a system enhancement package (SEP) by 2004. The M1A2 SEP contains an embedded version of the US Army's Force XXI command and control architecture; new Raytheon Commander's Independent Thermal Viewer (CITV) with second generation thermal imager; commander's display for digital colour terrain maps; DRS Technologies second generation GEN II TIS thermal imaging gunner+IBk-s sight with increased range; driver's integrated display and thermal management system. The US Army planned to procure a total of 1150 M1A2 SEP tanks, however future Army budget plans suggest that funding may not be available after 2004. Under the Firepower Enhancement Package (FEP), DRS Technologies has also been awarded a contract for the GEN II TIS to upgrade US Marine Corps M1A1 tanks. GEN II TIS is based on the 480 x 4 SADA (Standard Advanced Dewar Assembly) detector. ------[End Officer XXX's tutorial]----- Chuck Spinney "A popular government without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a prologue to a farce or a tragedy, or perhaps both. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance, and a people who mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives." - James Madison, from a letter to W.T. Barry, August 4, 1822 [Disclaimer: In accordance with 17 U.S.C. 107, this material is distributed without profit or payment to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving this information for non-profit research and educational purposes only.] Newhouse.com A Cautionary Tale In The British Invasion Of Iraq [Reprinted with Permission] With fluttering flags, glinting weapons and high expectations, the expedition set off into the interior of Mesopotamia confident of its military superiority, intent on securing the country's oil and capturing Baghdad for a brisk regime change. Instead, in a sobering lesson for imperial ambitions in the place now called Iraq, the British army campaign of 1915-16 was a colossal and costly blunder, a bloody, nightmarish tragedy of incompetence, slaughter and betrayal. Machine guns manned by entrenched enemy mowed down British troops by the thousands. For lack of medical care, many of the wounded and mangled were left in the sun for days. Thousands of British enlisted men, abandoned by their commanding general, starved or fell to disease. "It was a disaster," said retired British Air Vice Marshal Ron Dick, a military historian and author. For that reason, he added wryly, "Hardly anybody remembers it." Although the British lost almost as many men in three years as the United States did in nine years in Vietnam, American military officers are not required to learn about the ill-fated campaign and its grim aftermath. The subject is missing from the military history curricula at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, at the Army's Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kan., and at the U.S. Army War College at Carlisle Barracks, Pa. But the bloodletting is remembered by the families of the 51,800 British and Commonwealth troops -- mostly enlisted men -- lost in Iraq, including Pvt. William Wilby of the 2d Norfolk Regiment, who died of dysentery in 1916 while being held prisoner. Barely 22, he wrote home in 1915 to apologize for not writing more often: "I have not had the convenience, but I will try more in the future," he promised. Wilby is buried in Baghdad's North Gate cemetery in plot 21, row I, grave number 45. Britain was ultimately to prevail, but its imperial experience in Iraq, a 16-year occupation that ended in 1932, was no cakewalk, either. Its army found itself bogged down in turmoil and insurrection as clans and tribes revolted against military rule. Within two years, British officers were being assassinated on city streets with sickening regularity and violent anti-British demonstrations had become common, according to the U.S. Library of Congress country study on Iraq. In 1920, the British had to bring in Royal Air Force bombers to keep the peace. While there had been some optimistic talk of bringing democracy to Iraq, that generous impulse soon gave way to the harsher requirements of just keeping control. "I do not care under what system (of government) we keep the oil," British Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour wrote in 1918, "but I am quite clear it is all-important for us that this oil should be available." The British envisioned none of these difficulties when their forces landed at the southern port of Basra in November 1914. At that time oil -- as it is today -- was a major strategic consideration, "a first-class war aim," wrote Sir Maurice Hankey, secretary of the War Cabinet, as recorded in Daniel Yergin's 1991 history of Middle Eastern oil, "The Prize." Indeed, with the Great War under way on the continent, demand for oil was rising so quickly that gasoline was in short supply in England. The London Times warned its readers that private "`joy-riding' may have to go altogether." The invading force, under the command of Maj. Gen. Charles Townshend, was made up of bits and pieces of English and Indian units. But it was armed with gear considered not good enough for regular army, Townshend wrote to friends at home. He also complained about inadequate logistics support and poor communications, according to a recent account written by Air Marshal Dick. Townshend was intelligent, brave and charming, but also vain and dishonest, wrote Dick in a paper on leadership for the U.S. Air Force's Air University. Townshend was "an egotist driven by ambition and ravenous for popular acclaim. He craved honor, rank and the admiration of others." Nevertheless, Townshend's men quickly seized Basra and took a year to consolidate. In September 1915, still lacking logistics support, they launched up the Tigris River toward Baghdad, carrying six weeks' supplies. In 120-degree heat, 11,000 men slogged upriver, dragging their boats and guns through shallows. They were badly outnumbered by the time they reached the outskirts of Baghdad, where the defenders waited on both banks of the Tigris at the town of Ctesiphon. Half the remaining British force -- some 4,600 men -- fell in the ensuing carnage; the rest fled. Townshend had provided no field hospitals and insufficient medical supplies; those wounded who were lucky enough to be evacuated were floated downriver on barges that took 13 days of blazing sun and freezing nights to reach Basra. Townshend's retreating forces regrouped at the village of Al Kut 200 miles downstream, where Townshend estimated he had 22 days' supplies. The enemy laid siege. Townshend kept his beleaguered garrison of sick and wounded on full rations and food quickly ran out. The British made two futile attempts at rescue, accumulating some 23,000 casualties over three months of maneuvering. In one battle, the British Tigris Corps marched an exhausting 14 days, then charged straight into the entrenched enemy forces and was cut to pieces, suffering 4,000 casualties. Eleven days after the fighting, an observer found more than 1,000 wounded men still lying out in the open. By mid-April, Townshend's troops were starving. Men were dying of scurvy at a rate of 10 to 20 a day. Heavy rains and lack of sanitation spread disease. Men ate oxen, camels, cats. "The suffering of the troops was appalling," wrote Dick. Townshend offered to surrender, volunteering to turn over a million pounds sterling and all his guns, and promised that his men, if let go, would stop fighting. His offer was abruptly refused. Several days later Townshend surrendered unconditionally; the siege had lasted 147 days. According to the British government's official account, Townshend was whisked away to the pasha's luxurious palace in Constantinople, then capital of the Ottoman Empire of which Iraq was a part, where "he lived in comfortable captivity" for the rest of the war. Dick is more direct: While his men were dying by the thousands from disease and starvation, Gen. Townshend "was entertained at Constantinople's best restaurants and established in a splendid villa with his servants." His surviving men, including Pvt. Wilby, were marched, staggering under the blows of whips and sticks, to prison camps hundreds of miles away. One British officer, Capt. A.J. Shakeshaft of the Norfolk Regiment, came across a straggling column of the emaciated survivors and recorded his shock: "a dreadful spectacle -- British troops in rags, many barefooted, starved and sick wending their way under brutal Arab guards through an Eastern Bazaar -- (men) slowly dying of dysentery and neglect." Some 3,000 men died in captivity. Townshend was sent back to England and peaceful retirement. "The British army closed ranks" against any questions about his conduct of the campaign, Dick said. Wilby's mother, back home in the village of Earsham northeast of London, received a pension of five shillings a week and a letter from War Secretary Winston Churchill conveying "His Majesty's high appreciation" of Wilby's services. In 13 little-known cemeteries in Iraq today are the graves of some 22,400 British and Commonwealth soldiers. Late last year, the British government shipped 500 new headstones to Baghdad to replace those broken and corroded by weather. EYE ON THE GULF WorldNetDaily Excerpts: ... "If he lets loose with [the dams] he can really slow us down and create some problems," Lt. Cmdr. Pat Garin, executive officer of the Navy Seabees' 74th Mobile Construction Battalion, told the Herald. According to the report, U.S. troops are well-prepared to overcome water obstacles. They have brought nearly a mile's worth of erector set-like Mabey & Johnson bridge sections, several 210-foot Medium Girder Bridges and dozens of 60-foot Armored Vehicle Launched Bridges and floating bridge pontoons. ... Hussein could flood southern Iraq by destroying the Lak al Milh Dam southwest of Baghdad and two others on the Tigris and Euphrates, ... A Seabee officer said that parts of Mesopotamia are so muddy and wooded after the rainy season that his unit has considered switching from desert camouflage uniforms to the darker woodlands pattern to blend in better. ... "Even if bridges are up, we'll have to work carefully to make it across because if he's smart, those are going to be his kill zones." |