|

The Auerbach Report:

Was Lenin's Theory of Capitalists Hanging

Themselves Incomplete???

September 13, 2003

Comment: #493

Discussion Threads - Comments #s: 491, 489, 476, 470

Have the Neoconmen created the New Rome they so fervently desired ... or have they magnified the growing pressures to push the United States into a period of long-term decline???

Certainly, by militarizing our grand strategy, they have blackened America's moral stature in the eyes of the world [see Comment #491 and related Comments]. Moreover, they did this at a time when the free-lunch politics of front loading policy decisions practiced by both political parties have created tightening noose around the throat of the political-economy that glues together America's social fabric.

This Comment examines one strand in the rope that threatens to strangle our way of life, a problem that will be made much worse when the costs of supporting an aging population begin to explode at the end of this decade. The strand in question is woven out of twin deficits in the federal budget and the international merchandise trade balance.

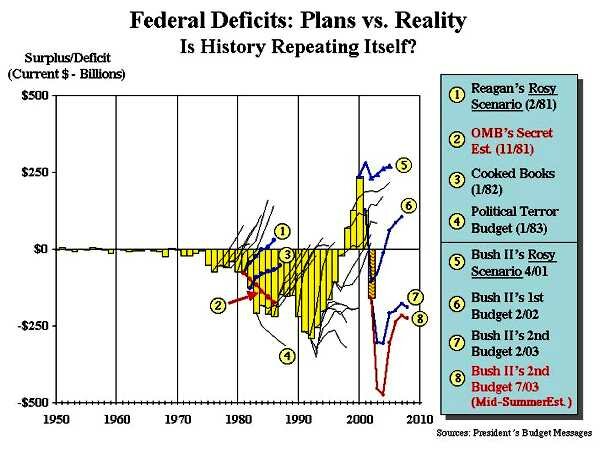

At the risk of being repetitive, lets look at these towers. Figure 1 compares history of the Presidents' projected federal budget deficits and surpluses (the lines) to the history of actual deficits and surpluses (the bars).

Figure 1: Federal Deficits

President Bush sold the country on tax cuts in April 2001 by predicting they would invigorate the economy and thereby increase jobs, profits, and standards of living, while producing an unending stream of surpluses in the federal budget (line #5). To date, as subsequent budget plans show and actual deficits show (lines 6-8 and the bar for 2002), this vision has not happened, notwithstanding three successive predictions of improvement. One reason is that the April 2001 prediction (line 5) was based on front loaded assumptions that misrepresented the future consequences of policy decisions being promoted.

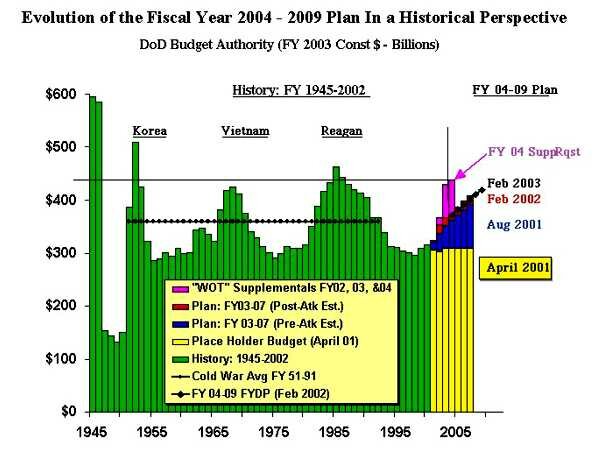

Included in the April 2001 prediction, for example, was the deceitful assumption that future defense budgets would remain constant in real terms (i.e., see the yellow bars in Fig 2 below), when, in fact, the Pentagon had been given the green light to add a huge out-year bow wave to the defense budget which was completed by August of 2001 (see the blue bars in Fig 2). The popular belief that 9/11 caused the entire explosion in defense is dead wrong. Fig 2 shows that the core program was put in place before 9/11. It also shows the War on Terror is now being paid for by supplemental appropriations while the cold war legacies in the core program, which have nothing to do with the War of Terror (like Star Wars, the F-22 jet fighter, and the new attack submarine), continue to be protected. Clearly, the projection made by the White House (OMB) in April 2001 misrepresented the future consequences of President's policy decisions in order to sell the tax cut to a Congress that was not interested in doing its homework.

Figure 2: Defense Budget

Bear in mind the front loading deception in April of 2001 was a time-proven ploy. Referring back to Figure 1: Note the projections made by the Reagan Administration between 1981 and 1983. That administration employed a similar sleight of hand to sell its tax cut and defense spendup. It downplayed the future consequences of its policies with two rosy scenarios (i.e., lines #1 and #3 in Figure 1) while hiding what they thought were the real consequences of those policy decisions (i.e., line #2 in Figure 1).

Events turned out to be even worse than Line #2 predicted and by the mid 1980s, the 1984 Terror Budget (line 4, Figure) and cries of an unfundable social security crisis (appealing to people's fear for their futures) were used together to bail out the imbalance by increasing the social security tax — the most regressive tax in our tax system. The surpluses in the social security trust fund thereby generated were used immediately to reduce the size of the federal deficit. The Bush front loading operation in 2001 and policy to fund the War on Terror on a pay as you go basis while protecting the Cold War Core Program is setting the people up for another regressive tax cut, because our government continues to squander the surpluses in the social security trust fund.

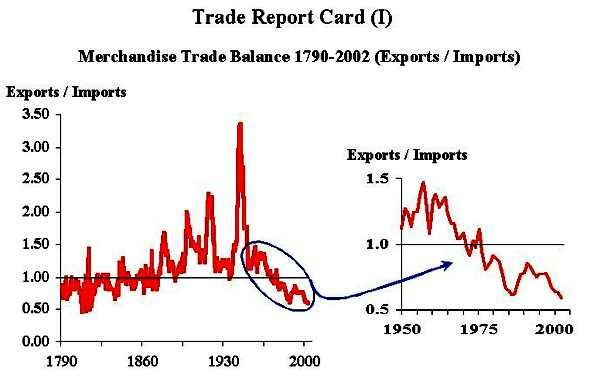

One is is beyond dispute: The federal budget deficit creates debt, and this debt exists in a country addicted to consumer debt. Federal debt does not exist in a vacuum. Other economic factors also impinge on this debt, not the least of which is the chronic problem of financing America's growing trade deficit. As Figure 3 below shows, America's trade merchandise trade balance has been deteriorating since the mid 1950's, and after some improvement in the 1980s, has been plunging since the early 1990s. Newspaper reports suggest that the 2003 trade deficit will be the worst in history.

Figure 3: History of the United States Merchandise Trade Balance — 1790 to 2002

The long-term decline in our merchandise trade balance stands in sharp contrast to our earlier — and far longer — history of improvement and progress as our country rose to greatness (as a republic, not an empire). When exports exceed imports, the cash flow produced by exports is not sufficient to buy the products being imported, and United States must make up the difference with money obtained elsewhere. How we get this money is an arcane subject, well beyond my expertise, but some form of borrowing is probably necessary.

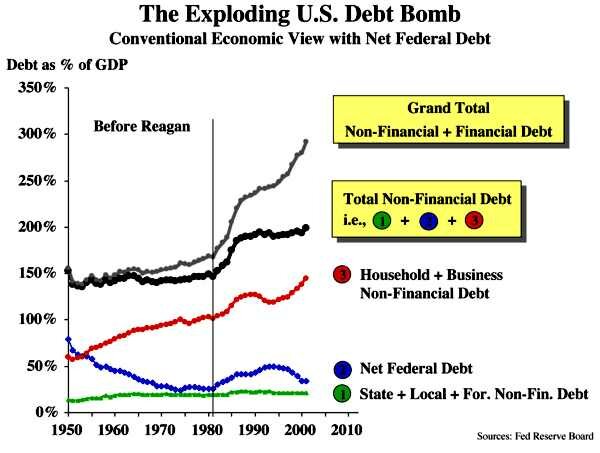

So the federal budget deficit and the trade deficit have a common denominator. Both are both related to debt, and as Figure 4 below shows, that total debt in the economy relative to the size of the economy has been soaring since 1980. As any consumer knows, a growing ratio of debt to income limits future freedom of action

Figure 4: Ratio of Debt to Gross Domestic Product

So, the trends of deficits and debt are ominous, but what do they mean, particularly in the context of the neocomen's dream of the New Rome???

I asked my good friend Marshall Auerback, a Canadian financial expert living in the UK, to explain the how the twin deficits are impacting America's freedom of action. Auerback is a financial advisor at David W. Tice & Associates, a Texas-based investment advisory firm, and is a frequent contributor to company newsletter, The Prudent Bear.

Attached is Auerback's eye-opening response to my question. I urge you to read it carefully.

|

Auerback Report: Why Lenin was Wrong

Marshall Auerback

September 16, 2003

Problem: The Kindness of Strangers is Killing America

The Fed's flow of funds data that was released last week more than ever highlights America's acute dependence on the kindness of strangers, particularly those of the Asian variety. Globalisation has been turned on its head. Instead of the centre lending capital to the developing periphery, capital is flowing back to the centre—that is, the United States.

Discussion

Even poor nations are lending the United States huge quantities of surplus capital, mainly to keep America afloat as the world's buyer of last resort.

China is the new "bad boy" of the global economy, having displaced Japan as the aggressive emblem of a trading system ferociously out of balance. Congress has begun making increasingly loud protectionist threats as a consequence. Even leading US cheerleaders for freewheeling globalisation (including Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan) have begun scolding China for excessive ambitions, just as they once criticized Japan, to no avail. The National Association of Manufacturers issued a report warning that 2.3 million US manufacturing jobs have disappeared since 2000, largely due to international competition (not entirely from China). The United States risks losing "critical mass" in manufacturing, says the NAM. A Defense Department technology-advisory group confirmed that so much "intellectual capital and industrial capability" has been moved offshore, particularly in microelectronics, that the Pentagon is dangerously dependent on foreign producers to make its high-tech weaponry.

If the United States falters and can no longer acts as the engine of global growth, the entire system is in deep trouble. Of course, the corollary also applies: With the current account deficit is at 5% of GDP for the first time in history, America's dependency on Asia's central banking fraternity is gargantuan. China, Japan, South Korea and Hong Kong now own a combined total of about $696 billion in Treasuries at the end of June about 46 per cent of the outstanding stock of bonds. China alone now holds $290 billion in US government debt, more than any other foreign lender, according to Chen Zhao of the Bank Credit Analyst Research Group. "The flow of Chinese savings has enabled Americans to borrow and spend more," he explained in the Financial Times. "China is glad to see Americans going on another shopping spree. Its factories are cranking up production at an unprecedented pace.... China's exports to the U.S. jumped 35 percent in the first quarter" compared with the first quarter of 2002.

If the US were a developing country, there would already be widespread speculation as to how long before the IMF was rolled in to help. Compare the situation to that of Argentina: Argentina's problem was too much debt for too small an economic engine. When foreigners stopped investing in Argentina, the music stopped and there were no chairs. The fervent hope of US policy makers is that the US economy will surge, its debt repayment capacity will grow, as the country grows its way out of a looming debt trap dynamic. But the arithmetic is hardly compelling support for such a benign outcome.

It is true that the potentially dire effects on the level of activity since 2001 has been mitigated by a transformation in the stance of fiscal policy, accompanied by a radical change in attitudes to budget deficits, which have suddenly became respectable (even under an ostensibly "conservative, small government" Republican administration). The expansionary fiscal policy initiated by President Bush was reinforced by a further aggressive relaxation of monetary policy so that (real) short term interest rates have fallen almost to zero, thereby giving the consumer boom a last gasp. Yet, with all this help, the recovery from the recession of 2001 has not been particularly robust. Growth has generally been below that of productive potential, jobs have been disappearing, and there is a widespread sense that all is not well.

Today, the US private sector financial balance is almost back to neutral after a long stretch since 1997 in deficit spending territory. Because low interest rates encourage households to keep borrowing and spending, the private sector has yet to return to its traditional net saving position of 1-2% of nominal GDP. Virtually all of the improvement has been on the back of the largest fiscal stimulus in history, as opposed to genuine balance sheet repair.

The deepening trade deficit has confounded the ability of fiscal deficit spending to push the private sector back into a net saving position. That means fiscal policy has had to go alarmingly deep into deficit spending to prevent a private income growth collapse. This is inherently unstable: the rate at which foreign debt has been accumulating is such as to generate a further, accelerating, flow of interest payments out of the country, which might necessitate even larger budget deficits in subsequent years.

Such is the current state of affairs that we now have the reappearance of the "twin deficits" so feared by bond investors in the first half of the Reagan Administration. Investors used to worry greatly about this condition and the dollar's trend was largely established each month by widely scrutinized trade reports which highlighted growing imbalances, even though the external condition of the US was nowhere near as dire as today. Then, America was still a net creditor, the current account at its worst never exceeded 3% of GDP, and the geopolitical circumstances of the era largely ensured the maintenance of the status quo, no matter how economically untenable longer term. The nations of emerging Asia built up their manufacturing apparatuses during the Cold War when they abutted major sites of "communism", which gave the United States an overriding interest in fostering their state-led capitalisms in order to prove that capitalism was superior to the communist systems next door. By the start of the 1980s, when the U.S. began to move from competing in manufactures to dominating through finance-and importing a rising fraction of manufactured goods-capitalist East Asia was well placed to ride the surge of U.S. import demand and even to provide out of its growing financial surpluses the savings needed to cover escalating U.S. current account deficits.

Things have changed somewhat today in the post cold war era. Asia is no longer a cold war ally, but a "strategic competitor", particularly China. Yet, in the economic sphere the US still relies on this old cold war construct: Asia exports its goods into a relatively open American consumer market, and then recycles its savings back into Treasuries. But as countless analysts are now warning, the risk of an external creditor revulsion may finally force foreign investors to demand a higher required return (that is, higher interest rates and lower stock prices) in order to both continue holding their massive US dollar denominated assets, and continue to purchase any new financing issued by US public or private entities. It is possible such demands could derail the US economic re-acceleration, and this must be considered the major downside risk at the moment.

The challenge ahead with regard to US financial balances is pretty clear: the US trade deficit must be reversed before the fiscal deficit peaks in 2004.

There is no indication the Administration recognizes this challenge, or is even exploring options to address it, beyond the current protectionist rumblings in Congress and the ineffectual if not counterproductive jawboning of Asia, especially China, on the issue of currency pegging. In fact, threats of increased protectionism to counter China's alleged "unfair" pegged rate monetary regime, might well prove counterproductive, given the extent to which the Chinese are now continuing to provide the fuel to motor further US economic growth, the very dynamic American policy makers hope will allow them to escape their debt conundrum.

Further complicating the picture is that too much growth abroad, ostensibly helping the trade deficit, creates other potential problems. Clearly, America's interest rate structure is closely tied to how well growth and investment demand proceeds overseas. This is why the pickup in the Japanese economy is probably the biggest story in global finance, yet it is getting only moderate attention. If that nation ever really did right its economic ship and sail off on a three or more year period of strong growth, the amount of upward pressure the US would experience on market-based interest rates could be astonishing, particularly in the absence of genuine balance sheet repair.

Conclusion

Thus, there is a troubling circularity to US economic policy making. Growth, which is an essential prerequisite to continued debt repayment, is largely fueled by further debt accumulation. And the countries that continue to perpetuate this paradoxical state of affairs, notably China, still face unremittingly hostile pressure from American policy makers to revalue the currency, thereby potentially precipitating the sort of dollar crisis that could well induce sharply lower growth in the US as foreign creditors demand correspondingly higher risk premiums to compensate for a fall in the external value of the greenback.

Given the precarious nature of America's predicament, one would have thought that a prime objective of diplomacy would be to cement good relations with its largest creditors, so as to minimize these economic vulnerabilities. Yet, just two years after the September 11 attacks, the opposite appears to be the case. Traditional alliances in Europe are marked by increased friction; for all of the talk of new "friendships" with Russia, the global economic system's prosperity ultimately rests on the US-EU alliance which, if it really breaks down, will take the global economy down with it. Cancun appears on a knife's edge.

As in Europe, the United States today is finding a new coolness in its relations with old friends in Asia. Whether in Tokyo, Beijing, Jakarta, or Bangkok, the analysis of US objectives and motives is sharply at odds with the standard American rationale. In their view, the US wants a strong and prosperous Asia, but only on American terms - economically sound, politically obeisant to Washington, and largely accepting of the American economic model.

This is also being reflected in the country's current negotiating stance in the impending global trade talks at Cancun. The rights of foreign capital and corporations are to be expanded; the rights of sovereign nations to decide their own development strategies steadily eliminated. A country must not require multinationals to form joint ventures with domestic enterprises. It must not limit foreign ownership of its natural resources. Capital controls are to be abolished. National health systems, water systems and other public services must be open to privatization by foreign companies. Underdeveloped countries must, meanwhile, enforce the patent-rights system from the advanced economies to protect drugs, music, software and other "intellectual property" assets owned by wealthy industrialists. Any poor nation that dares to resist the WTO rule will face severe "sanctions"—huge cash penalties—and possibly de facto expulsion from the trading club. On the other hand, any talk of eliminating agricultural subsidies is quickly shot down and left as a vague subject for future negotiations.

America's hard-line stance might be understandable were its military dominance matched by comparable economic might. But such a position is far less tenable when the US is the world's largest supplicant for global capital flows and fighting an increasingly expensive global war on terror. It is premised on lopsided power play which presupposes that an economically vibrant, strong America can easily press the weak to accede to their terms or else get nothing back at the bargaining table, and very possibly lose their access to foreign capital or development aid. But who is it that is most dependent on foreign capital at this stage?

Asia in particular appears to have learned its lessons well from 1997: policy makers in the region have concluded he who holds the credit, gets to choose when to pull the rug out from under the dependent debtor, and on terms fairly non-negotiable. At best, then, the imperial debtor can try to be cordoned of his consumers of global goods from such blackmailing creditors, thereby undermining their ability to accumulate further claims against him. But since it is in no small part US based corporations or subsidiaries operating out of export platforms in China and other Asian nation, this would be a hard one to pull off without the imperial debtor power slitting its own throat. Lenin's "sell them enough rope and capitalists will hang themselves" theory was incomplete. As China may have figured out, you have to sell them the rope on credit to really hang the little piggies high (or, at the very least, to keep the protectionist wolves at bay).

But the nexus between China and the US is fundamentally unhealthy and ultimately points to the fragility at the heart of the global economy right now.

China's "kindness" is in effect killing America. By allowing the US to buy more than it produces and borrowing to do so, it will eventually force an ugly reckoning. With its ever-swelling trade deficits, the moment of painful adjustment draws closer, but the debt cycle is unlikely to stop until creditor nations conclude that the US debt position is too dangerous and start withholding their capital. Alternately, if China's overheated economy gets mired in financial disorder or inflationary pressures, as appears to be the case today, it might need to bring its capital home—thus pulling the plug on American consumers and the "buyer of last resort" for the global system at large. It would certainly be nice to think that Washington's policy makers would act to deal with this looming threat, but it hardly seems credible with a Presidential election around the corner. Nor would an open acknowledgement of America's current economic failings be the sort of thing one would expect from a President who makes press conferences against the backdrop of aircraft carriers in order to project an aura of supreme American might. The dollar is beginning to roll over, and the US markets are having so much relative difficulty making headway recently in the face of an extraordinarily accommodative monetary and fiscal posture. All of this suggests an underlying awareness on the part of the markets' of the grave challenges facing America in the future.

|

Chuck Spinney

"A popular government without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a prologue to a farce or a tragedy, or perhaps both. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance, and a people who mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives." - James Madison, from a letter to W.T. Barry, August 4, 1822

[Disclaimer: In accordance with 17 U.S.C. 107, this material is distributed without profit or payment to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving this information for non-profit research and educational purposes only.]

|