|

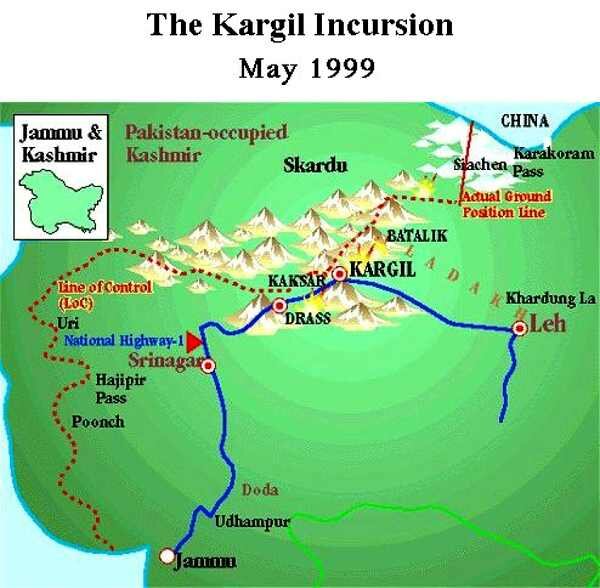

De-Colonizing Kashmir vs. Islamic Extremism & Hindu Chauvinism August 29, 2000 Comment: #382 Discussion Thread - #377 - "Kashmir and the Arrogance of Ignorance," #325 - "Coup in Pakistan-An Expert' Initial Observations." References: [1] Selig S. Harrison, To Push A Kashmir Settlement, Lean On Pakistan, International Herald Tribune, August 24, 2000 [2] Map of Kargil Incursion in Adobe PDF file as separate attachment. The confrontation between India and Pakistan over Kashmir may be the most dangerous in the world. It is the world's only shooting conflict wherein both belligerents have nuclear weapons. It is also a conflict about which most Americans, including me, know next to nothing, and there is growing pressure for the Great Nanny State to get involved. In the interest of learning more about this dangerous dispute, this comment continues Professor Harold Gould's discussion of Kashmir Question [see #377 and #325]. Recall that Prof Gould introduced us to the complexities of Kashmir Question by critiquing the proposal put forth by Congressman David Bonior proposal that the US intervene and broker another peace process [see Comment #377]. Bonior argued in a 31 July op-ed that the unilateral cease fire called by Kashmiri-based guerrillas (Hizb-ul-Mujahidin - hereafter called the Hizbul) presented America with a unique opportunity to ease tensions in the world's most dangerous conflict. But one of the premises underpinning Bonior's argument was the questionable belief that General Pervez Musharraf, Pakistan's leader, was trying to halt the insurgency in Kashmir and wanted to open discussions with India to reach a settlement. Gould countered by saying that Bonior's proposal betrayed a blatant anti-Indian bias that was rooted in flawed perceptions left over from great power politics of the Cold War. In fact, the Hizbul cease fire collapsed a week after Bonior's op-ed, because Hizbul alleged India refused to allow Pakistan's participation in the talks. This simple allegation may have masked a far more complex situation, as suggested by Musharraf's immediate belligerent reaction, ''Pakistan stands united with its Kashmiri brothers and sisters in their just cause,'' …l ''and will continue to extend all moral, diplomatic and political support to their indigenous struggle against state-sponsored terrorism.'' This quote is, to say the least, at variance with Bonior's simplistic premise In Reference 1, Selig Harrison takes a very different view of Musharraf's motives in an op-ed published in the International Herald Tribune on August 24. I will now briefly summarize his points, but I urge you to read his op-ed in its entirety. Harrison argues in that Islamic extremists based in Pakistan sabotaged the recent cease fire overture by the indigenous Kashmiri Hizbul guerrillas. Like Bonior, Harrison thinks the US has a window of opportunity to become involved in a peace making, albeit in concert with the international community. Instead of accepting Bonior's anti-Indian bias, Harrison advocates putting the squeeze on Pakistan by stiffening restrictions on IMF debt re-scheduling as well as new financial aid. He says the US is reluctant to do this because of a fear that economic restrictions could collapse Pakistan's already sagging economy. Finally, Harrison's recommendations are not one-sided; he would also squeeze India by arguing that any long lasting solution would have to award greater autonomy to Kashmir. Harrison's more balanced argument leads to a two-staged formula for a lasting peace, which he claims Kashmiris on both sides seem to favor: (1) Kashmir should remain within India's constitutional and defense framework, but with a degree of autonomy bordering on independence. (2) Pakistan keeps the portion of Kashmir it has occupied since the 1947 de-facto partition in the first India-Pakistan war. Will such a plan work, or are we being fed another dose of the Arrogance of Ignorance? Not having a clue to the answer to this question, I asked my friend Professor Harold Gould of the University of Virginia what he thought of Harrison's proposal. Here is Gould's response. As you will see, this issue is far more complex than it appears, and it has many subtle twists and turns, but in the end, Gould agrees that Harrison's viewpoint is far more substantive than Bonior's: Gould's Analysis of the Harrison Proposal Chuck—Selig Harrison is an excellent scholar-journalist who has been writing and commenting on South Asia and other parts of Asia for around four decades. The attributions to the conclusion of his recent International Herald Tribune article provide information about his current status. I believe he commenced his career on South Asian Affairs when he was NYT correspondent there back in the 1950s. Regarding the content of this article, I must say at the outset that Selig (or ‘Sig', as he is called) has got his facts right and his analysis mostly right. His point that the present Pakistan government is being held hostage to Islamic militant groups in the country is correct. His claim that "five of the generals in [Musharraf's] inner circle are powerful sympathizers" with the militants puts a bit of a quantitative face on the depths of the threat to his continuation in power. Harrison sees Musharraf as trying to survive by "appeasing" these factions. One question that arises, however, is the extent to which Musharraf is appeasing these elements as opposed to tacitly being sympathetic to and complicit in their militancy. To be sure, Musharraf's behavior can be viewed as appeasing the militants as long as one remains focused on his immediate interests, specifically, the degree to which he will do whatever it takes to remain in power. All politicians in positions of paramount power, especially dictators, pursue this aim with whatever resources they command. But Musharraf also PROFITS from the specter of powerful militants in his circle. I believe it gives him an excuse for having his political cake and eating it to. To understand my hypothesis about Musharraf's strategy, it is necessary to go back to the Kargil Incursion and its relationship to Musharraf's rise to power. THE KARGIL INCUSION [Comment: The map below orients the reader to geography of the Kargil Incursion. Reference 2 is an Adobe PDF file of same map for those readers with email browsers that read imbedded figures. In May 1999, Pakistani sponsored forces attempted to open a new infiltration route in the Kargil area and cut-off the Srinagar-Leh road (in blue), the lifeline of the Indian Army running parallel to the Line of Control. India claimed the infiltrators were made up of Pakistani army regulars (masquerading as Mujahideen) and a sprinkling of Mujahideen, specially trained and equipped by Pakistan in 40 staging camps near the Line of Control (LoC). CS]

Musharraf was one of the principal architects of the Kargil incursion. Militant groups supported by Musharraf's faction in the Pakistani military infrastructure and the intelligence apparatus (ISI) executed the infiltration operation behind the back of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, presenting Sharif a fait accompli. Sharif, despite his many faults, was inclining toward some kind of rapprochement with India. Recall that I made this point on 15 October 1999 in a memo first published on your D-N-I web site [see Comment #325]. Although this argument was poopoohed at the time, it has been subsequently confirmed. Sharif tried to wriggle out of his loss of legitimacy in the aftermath of Kargil. He fired his military Commander in Chief (Gen. Jehangir Karamat), who, ironically, had opposed the incursion. He then appointed Musharraf in his place, in effect, letting the fox into the chicken coop. Shortly thereafter, Musharraf staged a successful coup. He threw Sharif into the slammer, tried him a rigged court, and sentenced him to life in prison. So, the military prevailed in Pakistani politics, as it has done repeatedly, whenever the country's weakly developed civilian political institutions have lapsed into a crisis. But, as in the past, military rule is already showing signs of faltering, because generals are simply not a viable substitute for democratic institutions. An observation by Pervez Hoodbhoy, a thoughtful Pakistani journalist, in Dawn (Karachi, Oct 16. 1999) is worth noting in this regard: "While the motives for demanding an immediate return to democracy are perfectly understandable and laudable, this demand is based on an inadequate recognition of one fact so important that it overshadows all else. State power in Pakistan has always been distributed so that key goals have been set and prioritized by the military, and civilian governments have had the job of implementing them. This unnatural separation between goal-making and execution makes for a system that has crashed frequently in the past, and is destined to keep crashing in the future. The military has sometimes been invisible, and at other times visible, but has been ever-present as the hand behind the system. At this critical juncture of Pakistan's history it needs to accept responsibility for having contributed to the country's present political and economic situation, and be permitted to lead it out of the morass. My contention is that setting up a caretaker government will be a fruitless endeavor doomed to fail." HAVING HIS CAKE AND EATING IT TOO The unnatural separation between military goal making and civilian execution is the key to understanding why Musharraf's present conduct can be interpreted as an attempt to preserve a increasingly shaky dictatorship. On the one hand, Musharraf helped to create the Islamic militancy problem in Pakistan by using Islamic militants as an instrumentality in the Kargil invasion. Moreover, by continuing to support the insurgency in Kashmir, Musharraf is able to fuel and sustain the politico-military instability that besets the region. On the other hand, the continuing instability plays into his hands domestically and internationally: Domestically, it appeases the Islamic militants in Pakistan, while at the same time enabling Musharraf to claim he is protecting the more secular elements in Pakistan from the Talibanization of society. Internationally, he plays on the same fear of Talibanization (which he helped to create) to induce the United States and other Western powers into supporting his regime economically and diplomatically and tilt against India. This is what I mean when I argue he is pursuing a strategy of trying to have his cake and eat it too. So, I agree with Selig Harrison's recommendation that the United States should not succumb to Musharraf's political blackmail by offering him economic and other assistance. As Harrison avers, withholding aid "would strengthen, not weaken, General Musharraf's ability to pursue more restrained [and one might add, sensible] policies." One might go even further and declare that a Talibanized Pakistan, if indeed this should happen, would in the end prove to be no more unmanageable' than a Musharraf-led Pakistan that disintegrates due to the dictator's inability to cope with the factional forces that are undermining his ability to revitalize civil society or employ the country's economic resources (both domestic and incoming) to successfully turn the economy around. The decision by the Hizb-ul-Mujahidin to declare a unilateral cease-fire and try for an agreement with India over Kashmir raises at least two additional interesting issues, however. THE QUESTION OF TIMING First, the sequence of events surrounding this peace initiative needs to be carefully appraised. The received wisdom, enunciated by Harrison and au courant in the State Department, is that the cease fire proposal was merely a tactic employed by the Hizbul to gain an advantage over the competing insurgent factions "that have been receiving greater support from Pakistani intelligence agencies." This may be indeed the main reason for Hizbul's cease fire gambit, but before one shapes a policy grounded on this belief, an alternative hypothesis is worth considering. Perhaps the Hizbul gambit was itself a Pakistani intelligence maneuver whose purpose was to provide an opportunity for the Musharraf regime to acquire official standing at any bargaining table. This condition would have been created had negotiations actually occurred between India and this insurgent faction. But it is the timing of "when Islamabad pressured Hizbul to make its offer contingent on Pakistan's participation in the proposed talks" that is crucial here. Given his political situation, Musharraf's pursuit of legitimacy in the face of the perils to his domestic survival might well have lain behind such a maneuver. THE QUESTION OF 'DE-COLONIZATION" (i.e., AUTONOMY) Second, there is the question of the eventual disposition of Kashmir itself through whatever bargaining process ultimately takes place. It is interesting to see authorities like Harrison now strongly advocating a greater measure of autonomy for Kashmir as a necessary basis for building peace in the region. To be fair, all critics of both India and Pakistan on the Kashmir dispute have pointed out that the people of Kashmir deserve to receive a greater role in the determination of their political fate. But until very recently, this matter received superficial treatment by all parties. One of the reasons for this has been the assumption that the indigenous Kashmiris are insufficiently politically developed to be serious players in the bargaining process. Such a viewpoint reflects a dominant colonialist mentality of the Indians and the Pakistanis as well as Westerners. A number of parallels exist between the fate of Palestinian and Kashmiri Muslims that help to illuminate this importance of changing this mentality. I suggested as much in two articles published seven years ago (Times of India, Nov 5, 1993 and India Abroad , Dec 3, 1993): At that time, I argued that "The net result of the failure of the policy on Kashmir by all relevant parties is that the political situation there is now structurally analogous to that in Palestine. Both are at an impasse which can only be resolved by entirely new thinking which recognizes the fact that the legacy of bitterly acquired and sustained fixed attitudes by all parties which led to this impasse must be set aside before any further progress can be made … " … the first step … must be to recognize that the Muslims of Kashmir have achieved a new political identity that will have to be factored into subsequent negotiations … The capacity of the Palestinians to transform themselves into a politically indigestible entity through the mechanism of the Intifada finally forced a broad enough spectrum of Israeli public opinion to accept that which had hitherto been inconceivable to them – viz., that the leadership which the Movement had spawned could neither be suppressed nor wished away. It forced the middle-classes and moderates in both societies to seek a way out even if it meant that the old dogmas (Israel's refusal to recognize the existence of the PLO; the PLO's refusal to recognize the existence of Israel) had to be abandoned. Israel and the Palestinians bit the bullet, so to speak. India, Pakistan and the Kashmiris must do the same … "Whether or not it is called Intifada, Kashmir's Muslims have employed tactics similar to those employed by the Palestinians to successfully transform themselves into a new type of political force that neither India nor Pakistan can deal with in the old ways. They have already permanently altered the social order in the Valley by driving out the Pandits [Brahmans] who had dominated its cultural and political life for centuries and had relegated Muslims to subordinate status in their caste hierarchy. They have brought all normal government and administration in Kashmir to a virtual standstill and have defied all attempts by the Indian government to restore order either by the carrot or the knout … "In a very real sense, the roots of these troubles lay not in the act of accession per se, but in the fact that the Muslim masses in Kashmir really did not have a meaningful voice in that act, any more than they did when Pakistan decided to mount an invasion of their country in order to "save" them. Others acted "for" them and took their assent for granted … "As in Palestine, this voicelessness, this second-class citizenship in their own country, created the soil in which increasingly radical and intransigent protest grew. And there can be no doubt that the techniques developed by the Palestinians, who were perceived to be in a structurally comparable situation, acted as the model for this new wave of grass-roots mobilization … " Since 1993, the failure to recognize and accept the politically indigestible character of the emergent Kashmiri polity has in fact resulted in the escalation of violence to a level that now transcends Intifada and more closely approximates Northern Ireland prior to the precarious settlement that was recently achieved there. The current situation in Kashmir is, in fact, far more dangerous than in Northern Ireland or Palestine for at least three reasons: (1) the two states competing for supremacy in Kashmir are nuclear powers, (2) a series of shaky Pakistani regimes have found that promoting terrorism and insurgency in Kashmir helps to deflect social discontent at home, and (3) Indian politics has gravitated toward Hindu chauvinism through the 1990s. CONCLUDING REMARKS I believe Harrison is correct in concluding a combination of partition along the existing line of control, plus "a degree of autonomy bordering on independence," is "the only realistic basis for a long-term settlement." Ironically, such a settlement could have been had as early as 1946, at the time of the Partition that created India and Pakistan as separate states. This is what the most important Kashmiri leader of that time, Sheikh Abdullah (the father of Dr. Farooq Abdullah, the present chief minister of Kashmir), wanted. For this reason, Sheikh Abdullah was imprisoned by the Maharaja prior to Independence, distrusted by the Pakistanis at the time of their proxy invasion of Kashmir, and following Independence again imprisoned by the Indians for fourteen years. Now it is clear that Farooq is evolving toward the same position that his father held. This is the inevitable manifestation of a Kashmiri identity that is continuing to evolve even as we speak. The legacy of Cold War politics and US involvement in the Kashmir dispute was discussed in my earlier essay on Kashmir [Comment #377] and need not be repeated here, other than to say that an eventual solution CANNOT be engineered or brokered by the United States. Our past policies make it impossible for the principals to view us as a neutral broker in this dispute. Only India, Pakistan and the Kashmiri people can make the peace. It has to come from within. Professor Harold A. Gould ---[end]---- Chuck Spinney [Disclaimer: In accordance with 17 U.S.C. 107, this material is distributed without profit or payment to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving this information for non-profit research and educational purposes only.] Map of the Kargil Incursion in .pdf format |