|

Is War a Business? or Why it is Necessary to Teach August 7, 2001 Comment: #423 Discussion Thread - Comment #s 169, 364, 381, 383, 386, 391; New readers might also want to consult #s 61, 72, 102, 114, 117,130, 131, 146, 154, 159, 166, 184, 193, 328 Attached References: [1] Elaine Grossman, "Rumsfeld Rejects Linchpin Force Structure Findings In Major Review," Inside The Pentagon, July 19, 2001, Pg. 1. Attached. [Reprinted with permission] [2] Thomas E. Ricks, "For Rumsfeld, Many Roadblocks: Miscues -- and Resistance -- Mean Defense Review May Produce Less Than Promised," Washington Post, August 7, 2001, Pg. 1 [3] Sharon Weinberger, "Rumsfeld Promises Change In Strategy, But Analysts See Little Difference," Aerospace Daily, August 7, 2001 [4] Otto Kreisher, "Effort To Remake Military Erodes Into War Over Turf," San Diego Union-Tribune, July 29, 2001, Pg. 1 [5] Rowan Scarborough, "Bush's 'Strategy First' Vow Scrapped, Review Officials Say," Washington Times, July 23, 2001. Separate Attachments: [6] Figure 1: Two Perspectives on US Defense Spending vs. the World (Adobe pdf format) References 1-5 make it clear that Secretary Rumsfeld's much ballyhooed top-to-bottom defense review is degenerating into yet another old-fashioned Pentagon food fight. The military services are battling each other and the Secretary of Defense, aided and abetted by flank attacks from their wholly-owned subsidiaries on Capital Hill, as well as their partners in the Defense Industry. The sorry state of affairs depicted in these five reports is bad news for the taxpayers and the soldiers. Left to itself, the internecine squabbling will push military deeper into its death spiral at an ever higher cost. Old time readers will recall that the Defense Death Spiral is a product of three structural problems—a modernization program that cannot modernize the force, the rising cost of low readiness, and a corrupt accounting system that makes a mockery of the checks and balances in the Constitution. While these three intertwined problems are the source of the chaos, they exist independently of questions of strategy or budgets—a fact that now seems to have been lost in the chaos depicted in References 1-5. [New readers can find a more detailed discussion of the causes of the Defense Death Spiral at

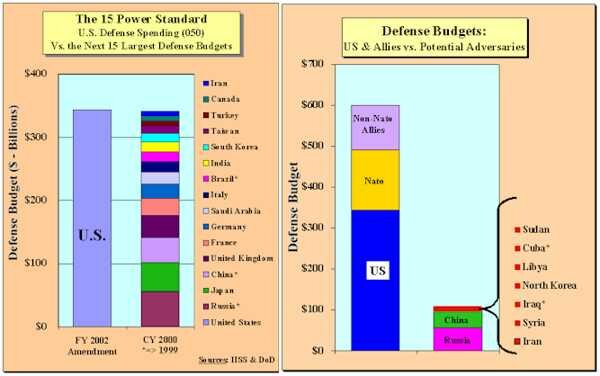

What is truly amazing about the chaotic state of affairs described in References 1-5 is that it is occurring at all. As Figure 1 below shows, the United States will soon be outspending the next 15 largest national defense budgets combined (assuming the FY 2002 Amendment is approved by Congress). It also shows that the U.S. will be spending over three times as much as the combined total of all its potential adversaries (Russia, China, and the 7 "rogues"). Add in the effects of our allies, and the favorable spending asymmetry increases to 5.5 to 1.

Figure 1 So, why isn't the Pentagon in fat city? Get ready for another chorus of feel-good "reform" centered on the idea that it is time to bring common-sense business practices to the Pentagon. The idea that modern business practices can shape up the military has been an article of faith among the defense cognoscenti at least since the McNamara "reforms" of the 1960s, if not the earlier reforms promulgated by Elihu Root at the beginning of the twentieth century. Yet, as these business practices became more pervasive via a system of continuous reform, the confusion and disorder paralyzing the Pentagon's senior leadership has increased steadily, and the death spiral has worsened. The chaotic deterioration of the last three years has created a sense of desperation among the cognoscenti. In some cases, the desperation borders on outright hysteria. Robert Kagan, for example, actually compared the "poverty" of the defense budgets portrayed in Figure 1 to the defense budgets that existed just prior to Pearl Harbor [see Comment 421]. John T. Correl, the editor of Air Force Magazine, made an equally irrational portrayal of my work to justify his call for defense budget increases to 4% of GDP—a proposal that would push the parsimonious budgets in Figure 1 to higher levels—far higher, in fact, than the highest budgets of the cold war [see Comments #391 and #386, for a graphic of the 4% Solution, see here. Maybe it is time to step back and quiet down, take a calm breath, and begin to examine the more basic tenets of our defense problem. Before adopting any more "business reforms," particularly those that promise to protect the status quo by financing it with predictions of future savings, perhaps it is time ask if the defense business is in fact a business. The attached opinion piece questions this basic assumption from a somewhat different angle. The author, John Brinkerhoff, an old friend, is a retired Army colonel and graduate of West Point. It is a stand-alone essay and was written independently (and therefore should not be viewed as an endorsement of my views). War is Not a Business By John Brinkerhoff One of the favorite fantasies of many defense intellectuals is the idea that war is just another business that can be managed by best business practice. This is nonsense. War is not a business, never has been, and never will be. A major problem with current attempts to make war more like business is that the appropriate measure of success is not well understood by the businessmen brought in to make DOD more efficient. The correct measure for business is to compare peacetime costs with peacetime effectiveness. The correct measure for war is to compare peacetime costs with wartime effectiveness. If the true measure for DOD were peacetime costs versus peacetime effectiveness, the best solution would be to eliminate the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps except for those forces actually conducting various operations other than war. This would provide a low peacetime cost devoted entirely to performing peacetime work. When a war appeared to be likely, the armed forces would be expanded just in time to deal with it. Don't laugh. This was the military policy of the United States from 1789 to 1950. The trick, of course, is to know when the wartime forces will be needed. One of the consequences of the peacetime-to-peacetime comparison is continuous pressure to cut overhead, infrastructure, bases, and other support activities that are excess to peacetime needs. Obsession with peacetime efficiency means that the fighting forces will very likely lack sufficient support and an adequate infrastructure when war comes. There is nothing less businesslike than battalions without soldiers, ships without fuel, aircraft without missiles, or troops without bullets. The business mentality fails to appreciate and fund preparedness measures to expand capabilities rapidly in the event of war. War is almost always unexpected and fails to conform to preconceived notions. Even small wars, such as the Persian Gulf War of 1990-1991 and the Serbian War of 1999, require extraordinary efforts. Preoccupation with cutting peacetime costs means that urgent surge actions will have to be taken to support wartime operations. Yet, the same mentality regards funding for wartime surge preparations to be wasteful instead of prudent. This kind of thinking leads to DOD budgets concerned primarily with peacetime costs. Annual budgets are the principal peacetime product of DOD—in collaboration with OMB and Congress. Business budgets tend to balance peacetime costs with peacetime operations. War budgets ought to balance costs for peacetime operations and costs for wartime preparedness. Within reasonable limits, the size of the defense budget is not as important as its composition. In fact, very often more money can make problems far worse. Smaller budgets can be viable but they ought to have a higher proportion of wartime readiness programs. It is hard for businessmen to realize that the best budget for war stretches scarce peacetime dollars by spending some money on war preparations that can be done rapidly when needed using plentiful (or at least less scarce) wartime dollars. One of the most damaging manifestations of the business mentality is the propensity to eliminate facilities and bases without regard for wartime requirements. Cutting bases is most harmful when the Government relinquishes land, air space, and sea areas needed for the training of troops in both peacetime and wartime. Military training is already limited by lack of space and environmental constraints. When DOD gives up large tracts of land to save a few peacetime dollars or avoid political controversy, it will never be able to get them back to support a major war even by spending many wartime dollars. It is difficult to understand why best business practice is thought to be a panacea for the problems of DOD. There is plenty of evidence that business practice is often wrong. Many businesses have blundered or gone bankrupt. What about the Edsel, New Coke, and Firestone tires? What about Hechinger's, Crown Books, and Montgomery Ward? What about the many ".coms" that have vanished without a trace? War is too important to be left to the businessmen. DOD is the proof. After a half century of being run by businessmen and bureaucrats, DOD is in bad shape. Accounting systems are inappropriate; auditing results are inaccurate; personnel management is in disorder; and the procurement process is a mess. Turbulence is the order of the day, accompanied by micromanagement and complicated reporting systems that fail to help the management of the enterprise. If DOD were a business, it would be bankrupt. Accounting systems are important, and they ought to reflect the true business of an enterprise. DOD's accounting systems are designed for peace and are inappropriate for war. Business accounting systems tend to focus on costs; war accounting systems ought to focus on the tasks that have to be done to implement the national security strategy. Not all business methods are bad for DOD. Some can be put to appropriate use if their application is tempered by constant appreciation of their impact on the ability of DOD to wage war. It is time that the businessmen in charge of the military establishment realize that it is their duty to use peacetime funding to provide wartime capabilities. Peacetime parsimony leads to wartime waste. "Businesslike" emphasis on peacetime operations will lead in the future as it has in the past to initial military disasters followed by a massive, inefficient effort to obtain the capability needed to win the war. Using peacetime dollars to assure wartime capabilities does involve "waste" in the sense that it is necessary to spend more than is necessary to support DOD's peacetime operations. That "waste" is needed is needed to maintain a capability for wartime operations. Military people understand that. Businessmen do not. End Brinkerhoff Opinion Piece Many people are attracted by analogies of business to war. After all, business and war are about competition and conflict, they are also about survival and growth. But in business, the form of competition is very different from that in war. War is a direct zero-sum interaction among two or more adversaries, whereas businesses compete with each other indirectly through an interaction that is mediated by third parties—the consumers. Decisions by consumers create a market, and the third party mediation of a market creates quasi-objective opportunity costs for the business competitors. These opportunity costs provide a business decision maker with a rational basis for comparing or trading off the costs and benefits of incommensurable but nevertheless competing courses of action. Defense decisions during peacetime, on the other hand, are mediated by the subjective competition produced by the domestic politics of the military - industrial - congressional complex - the MICC. As Brinkerhoff correctly points out, the subjectivity of these decisions is increased even further by the fact that peacetime decisions are disconnected from the wartime interaction that determines their true effectiveness. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that business practices predicated on the natural objectivity of a market interaction can not cope with the politicized subjectivity implicit in the peacetime defense "market." Decision makers in the defense "business" clearly need to appreciate opportunity costs of different courses of action, or in the present case, inaction. But they do not have a natural system like a market to manufacture this information. That is the central problem. I believe it is possible to construct an information system that would manufacture enough information to render an appreciation of these opportunity costs—or more precisely, the tradeoffs between incommensurable but nevertheless competing courses of action. My proposal for commensurating the incommensurable is contained in the final sub-section of the last chapter of Spirit Blood and Treasure (SBT), entitled "Teach the Pentagon to Think Before it Spends." It describes a disciplined three-step approach to providing the information system needed to give a decision makers a better sense of the real choices they face. Armed with such information, today's decision makers can the long-term trade offs needed to place the Defense Department on a healthy evolutionary pathway into future, without descending into the spookiness of Visions. In short, I contend the Pentagon CAN evolve a defense strategy that works in the real world or the 21st Century—a strategy that does not have to set the stage for a budget war between retiring baby boomers and the MICC early in the next decade. All it takes is a commitment to acknowledge, understand, and fix what is obviously broke. Chuck Spinney [Disclaimer: In accordance with 17 U.S.C. 107, this material is distributed without profit or payment to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving this information for non-profit research and educational purposes only.] Rumsfeld Rejects Linchpin Force Structure Findings In Major Review [Reprinted by Permission of Inside Washington Publishers: This article may not be reproduced or redistributed, in part or in whole, without express permission of the publisher. Copyright 2001, Inside Washington Publishers.] Three days after a final briefing was to have been presented that would incorporate all the findings of the Pentagon's Quadrennial Defense Review, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld tossed out a pivotal element of the far-reaching assessment: his study panel's recommendations on the future size and shape of the U.S. armed forces. The defense secretary has said he intends to utilize the QDR to develop transformational changes for the military so it can adapt to the threats it will face in the 21st century. The Pentagon, said one official, is "reeling" from Rumsfeld's July 16 decision to reject review panel recommendations that the defense secretary reportedly referred to as "a joke." Although many in the military agree with Rumsfeld's appraisal of findings from his "integrated product team" on forces -- which called for an unfathomable 34 Navy aircraft carriers and a reduction to perhaps as few as two Army divisions, defense officials tell Inside the Pentagon -- the QDR process by nearly all accounts is in a state of disarray. At a press conference yesterday (July 18), though, Rumsfeld sought to get out ahead of the news, acknowledging a hiccup with the force panel conclusions but assuring reporters, "I don't think any panel went wrong." Over the past four weeks, the Defense Department leadership has pushed the QDR toward completion at a "forced march pace," as a senior defense official told reporters in June, but the review is already at least a week behind schedule. A final briefing by a panel charged with integrating all the QDR recommendations into a single report -- originally scheduled for July 12 and 13 -- has been put off repeatedly. At press time, no new date had been set for the QDR's "integration group" to present Rumsfeld and his senior leadership with the overarching briefing, defense sources said. Pentagon civilians and military officers alike describe a QDR process that has gone awry. It started when, after four months of consulting with outside advisers gathered into ad hoc "strategic review" panels to stimulate and inform his thinking, Rumsfeld finally turned to his newly assembled civilian leadership and the military to begin work on a document that would guide the official QDR process. On June 22, he issued a highly detailed "terms of reference" paper numbering two dozen pages that outlined not only the mechanics of the major review, but also included substantive elements of a new military strategy (ITP, June 14, p1; and June 28, p1). But the document stopped well short of serving as a national security strategy, which Bush advisers said last fall was an essential conceptual basis for making critical overhauls in policy and programmatics at the Defense Department. "If you start from the top down, you start off with, 'Well, what are you planning against?'" a key Bush defense adviser told ITP last fall (ITP, Nov. 2, 2000, p1). Only with a clear national security strategy in hand could the Defense Department develop threat scenarios and determine what an appropriate force structure would be, this adviser said at the time. Yet the Bush administration has missed a mid-June deadline to submit the national security strategy to Congress, as required by the law laying out requirements for the QDR, and no defense officials interviewed said they'd even seen a draft of the document yet. Rumsfeld on June 21 told a House committee that national security adviser Condoleezza Rice "is working on" the comprehensive strategy, but "I forgot when she's required to do that." The quadrennial review got under way and is steaming toward conclusions without an overt security strategy, according to Pentagon officials. Terms of reference In that strategy void, the terms of reference -- which has come to be known in the Pentagon as simply the "TOR" -- has taken on singular importance as the central focus to guide thinking as the QDR has unfolded. Although the document reveals a distinct bent toward the notion that highly networked technology can provide an edge for U.S. forces against future adversaries and allow for the retirement of more cumbersome and less efficient "legacy" equipment, the TOR is also a hodgepodge that offers virtually something for everyone, many in the Pentagon have observed. "There are words in the TOR that you can find that you'll like, no matter what your equity is," said one Pentagon military officer. The document identifies 13 "priorities for investment" ranging from quality personnel to military experimentation to intelligence to missile defense to high-tech information operations to precision strike to rapidly deployable maneuver forces to unmanned systems to command and control to strategic mobility to countering weapons of mass destruction to modern logistics to "pre-conflict management tools," referring to crisis management using information technologies and small joint task forces, among other things. The TOR set in motion seven integrated product teams to undertake analysis in the review, and many of those spawned "sub-IPTs" to further delegate work. The more than 50 study teams -- which one official told Inside the Pentagon were "breeding like drunken muskrats" -- in many cases overlapped with one another in responsibility, sources said. Each IPT looked to the grab bag of mandates laid out in the terms of reference document and found justification for almost any approach participants sought to pursue, several Pentagon officials complained. Not surprisingly, many groups came to conflicting conclusions that defense officials say is now proving a daunting task to sort out and synthesize. Despite the official Pentagon statement that Rumsfeld would "cherry pick" recommendations from his earlier "strategic review" to include in the QDR, the official study teams largely have ignored those findings because the TOR does not account for how they would be incorporated, defense sources said. The TOR also sets the bar so high in terms of the quantity of missions uniformed personnel must undertake, and the conditions for military success, that defense officials point to the document as a principal culprit for some of the more unusual recommendations being generated by the major review. Meeting with reporters at the July 18 press conference, Rumsfeld acknowledged one of the QDR study panels presented conclusions that were skewed by "ambiguities" in the TOR, but steered clear of volunteering many specifics. "There were . . . apparently some ambiguities in the terms of reference, and the panel came back with some work that reflected those ambiguities, in their minds. And now that work is being redone." He said the panel "came back with some [force] cases that were larger, some cases that were smaller, some instances where it didn't seem to fit what we had had in mind when we crafted -- we thought we crafted -- the terms of reference." Rumsfeld also said the Pentagon leadership would revisit the text of the TOR and make changes as a result of the disconnects that were discovered. "Obviously, it's undoubtedly our fault, those of us who agreed on it, the terms of reference," Rumsfeld conceded. "So we went back and asked ourselves how that might have happened and what might have been the case. So we're just looking at it. It's no one's fault. It's one of those normal things that happens." Thirty-four aircraft carriers As it currently stands, the TOR states that the quadrennial review must "identify a wider range of mid-term and long-term contingencies and options for employing U.S. military forces, including for pre-conflict operations." And, it says, the United States must "deter aggression by maintaining regionally tailored forward stationed and deployed forces that are capable of swiftly defeating an enemy's effort with minimum reinforcement." Both statements would seem at variance with then-candidate George W. Bush's speech at South Carolina's Citadel in September 1999, where he decried "open-ended deployments" and the Clinton administration's use of the military for "engagement" missions as a way of preventing wars. Rice, Bush's national security adviser, said early this year the administration would undertake an "immediate review" of overseas military deployments, from Kosovo to the Persian Gulf and beyond. But the TOR's call for forces around the globe that could defeat adversaries with minimal reinforcement was said to be the basis for the 34-carrier recommendation by the QDR study team on force structure -- reportedly at the initiative of Michael Gilmore, a deputy director at the Pentagon's program analysis and evaluation directorate. It was thought that forces would have to be substantial in size to be either in place in a region or to rapidly respond when a crisis emerges, without drawing on extensive reinforcement from U.S.-based units. (Sources said the 34-carrier figure embraces the typical assumption that just one-third of carriers in the fleet are deployed at any given time, meaning about 11 could be sailing around the globe in this concept of "forward presence.") While Rumsfeld reportedly discarded the finding out of hand for its fiscal and political impossibility, this and other recommendations rising to the surface in the QDR beg the question of whether the defense secretary and his subordinates bit off more than they could chew as they launched the major review, Pentagon sources said. Not even the $329 billion the Pentagon has requested for defense in fiscal year 2002 can pay for the plans on the books developed by the Clinton administration, let alone the new initiatives Rumsfeld foresees in transforming and modernizing the military, defending against missiles and terrorist attacks, expanding information warfare and space combat capabilities, operating in urban environments, and experimenting with new warfighting concepts for the future, defense civilians and military officers are concluding. Few observers expect significantly more funds to become available for defense in coming years. "This is a reality-free zone," said one official in attempting to describe the current status of the review. Last week, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Hugh Shelton made news when he acknowledged he'd told Rumsfeld there was insufficient information on which to base some decisions being considered in the QDR. His concern echoed remarks officers had been making quietly for weeks -- most recently in regard to an assessment of rapid-response forces that, for lack of rigor, devolved into a service-versus-service bidding war (ITP, July 5, p1). The nation's top military officer's assessment stood in stark contrast to status reports the defense secretary has been getting regularly from his special assistant charged with shepherding the review, Stephen Cambone, senior defense officials tell ITP. One Pentagon civilian reports having heard Cambone tell Rumsfeld repeatedly over the past few weeks how "swimmingly" the QDR is progressing, despite reports of a proliferation of study teams rushing to judgment on critical national security issues and growing clashes between civilian and military officials (ITP, June 21, p1). Through a spokesman, Cambone declined an interview request this week. His nomination to become the principal deputy under secretary of defense for policy is pending before the Senate. With final reports beginning to come in from each of the QDR's integrated product teams, Rumsfeld and Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz "now see on their desk what we saw coming a few weeks ago," one senior military official said. None of the results are yet of "decision quality," another official said this week. No new date had yet been set this week for Rumsfeld to be briefed on the QDR's integrated results because so many inputs into the final product remain in flux, sources said. A meeting of the "executive working group" on the QDR, chaired by Cambone, to determine "the way ahead" had been scheduled for July 17, but was cancelled at the last minute because of the uncertainty, officials said. One of the QDR integrated product teams -- a study panel on "capabilities and systems" co-chaired by Pete Aldridge, the Pentagon's acquisition czar, and Barry Watts, the director of program analysis and evaluation -- has developed a briefing on modernization that lists several controversial options for programmatic overhauls. But few officials anticipate many significant weapons acquisition changes will ultimately be made. The panel has developed an option to cancel the tri-service Joint Strike Fighter, ITP has learned. But a growing chorus of support for the new attack aircraft among Rumsfeld advisers make this an unlikely QDR recommendation, sources said -- despite the fact that the aircraft's early stage of development might make it a more vulnerable target for cancellation than mature acquisition programs. Like many of the recommendations that have found their way onto QDR study team briefing charts, the option to cancel JSF was "just an option that somebody in [the Office of the Secretary of Defense] came up with," but it was not seriously considered by the capabilities-and-systems integrated product team, said one defense official. "We're not sure what's real" because it remains unclear which specific initiatives originated with Rumsfeld or Wolfowitz, and which ones alternatively were generated by mid-level "analysts floating their own ideas to see if they fly," said another Pentagon official. "I think lots of options have been presented, but nobody really knows what's serious." Aldridge's modernization briefing charts also cited an interest in applying additional funds over the next six years to the Navy's DDG-51 destroyer and Virginia-class submarine, according to one Pentagon civilian. Some officials questioned the basis for the proposed plus-ups to Navy ships, noting that naval combat capability was not overtly listed among the investment priorities laid out by the TOR. But Rumsfeld has voiced concerns on several occasions in past weeks about the Navy fleet dropping to well below 300 ships in coming years. An option in Aldridge's briefing to double production of the Air Force's F-22 fighter was included on early charts but removed before a presentation to Rumsfeld, sources said. Whose review is it? Some senior Pentagon civilians lay blame at the feet of the military for resisting major changes that would, in the Bush administration's view, better prepare U.S. forces for the kind of threats they may increasingly face. They depict an orderly QDR process in which early broad concepts were translated in the past couple weeks into specific recommendations -- at which point the uniformed military threw up obstacles to change. But with Rumsfeld having made clear early on that the QDR is the civilian leadership's responsibility to undertake -- with the military in a supporting role -- some find it mystifying that the administration may concede to the military the power to stand in the way. "I would be really concerned about what it means in terms of my ability to be a civilian authority," said one official. While many Pentagon officials agree the service chiefs have questioned a number of the proposals for change laid on the table by the QDR's civilian leadership, military officers see it as their role to advise the defense secretary about the risks associated with proposed alternatives. "Don't ask us to do something we know will come out really bad . . . or would injure national security," said one officer. In fact, the law calls on Shelton, as chairman of the Joint Chiefs, to formally assess the risk associated with the QDR's findings. Both the main QDR report -- for which the defense secretary is solely responsible -- and Shelton's risk assessment are due to Congress Sept. 30. Rumsfeld is already publicly lowering expectations that the QDR will result in major change, at least in the near term. "There are pieces of this that there simply is not going to be time between now and August [in which to complete] the analytical work," the defense secretary told a group of reporters on July 11, the same day Shelton expressed his concerns. He said some decisions would be made in time to craft the FY-03 budget, while others could be deferred to additional studies that may take as long as two years to complete. Judging from the amount and quality of work done to date, military and civilian officials said they expect Rumsfeld will issue his Defense Planning Guidance document around July 25 to inform the FY-03 budget development process. But the DPG will leave a number of key issues unresolved that were earlier discussed as the meat and potatoes of the quadrennial review, sources said. To many military officials, these critical issues are better left unresolved than rushed through a process that has been driven more by the practical and political considerations of building an FY-03 budget than by considered reflection on the current and future security needs of the nation. "I'm concerned that we're so late in the game on this that I don't know how you fix it without carefully lowering expectations," said one Pentagon source. At the same time, military officials reject the notion that they are resistant to change. The service chiefs yearn for change that will allow them to maintain readiness to perform current operations while better preparing their forces for the future, uniformed sources insist. The military chiefs had hoped fervently for more defense dollars -- and built up lofty expectations when Dick Cheney promised during last fall's campaign that "help is on the way" -- but they now recognize that the president's top-priority tax break and a shrinking budget surplus will preclude a big boost to the defense budget and necessitate more creative thinking. Some on the military side of the Pentagon say they launched much of that thought process last year as the Joint Staff led preparations for the coming quadrennial review. But Rumsfeld and his top deputies have shown little interest to date in exploring the work done by the military (ITP, May 24, p1). "It's not like they came in and saw the 'Planet of the Apes' wearing uniforms," one officer quipped, noting that the military takes seriously these monumental issues facing the nation. Blood on the floor Is a desire to demonstrate civilian authority over the military blocking a constructive dialogue? As the QDR process was being launched, one defense civilian reports hearing an official close to Rumsfeld boast that the Pentagon's "floor is going to run red with military blood." Several officials -- civilian and military -- say Cambone missed an opportunity to set a productive tone or build a functional process for the QDR. "As an individual, he has precious little respect for the military," griped one Pentagon official. Cambone "tends to dismiss" military perspectives, "to the point of not listening," said this source. "I find it hard to believe Rumsfeld puts so much trust in Steve Cambone," said one Pentagon civilian. Many officials interviewed noted what appears to be Rumsfeld's own genuine interest in a civilian-military dialogue. Several observers see a disconnect between Rumsfeld's hours and hours of immersion in QDR discussions with the Joint Chiefs and the contrasting tack reportedly taken by Cambone in discussions with his military counterparts. Officials are perplexed by the seeming polarity. While Cambone sometimes appears to be out of sync with the secretary, Rumsfeld has repeatedly tapped Cambone as a top lieutenant on defense study projects over the past few years and hand-picked the official as his special assistant on the QDR. But one source said an integrity problem with the QDR process is much broader than one deputy alone. "Rumsfeld's brain trust is not serving him well," according to this official. The source said no one should be surprised that the military will seek to avoid the risks associated with sweeping change, but that it is feasible to bring the uniformed leaders along in an overhaul. The official said there is a tendency among some of Rumsfeld's key deputies to "placate the four-stars" when the military leaders raise objections to specific proposals for change, rather than to work with the Pentagon brass to achieve the mutual objective of better matching ends to means. At the same time, some defense sources say Shelton's Joint Staff representatives have tended to offer little constructive help in QDR meetings. Some officials voice the impression the Joint Staff is standing by to offer criticism -- via Shelton's formal assessment -- only after the process is essentially done. No one has given up yet, though, observed one uniformed official. "There's more game to be played," said this officer. "We may be in the seventh inning." But the officer did not rule out the possibility that "the outcome is a foregone conclusion" in the minds of the top Pentagon civilians and "we are going through the motions." Following Rumsfeld's recent moves, many in the Pentagon are holding their breath for what is next. "It's a question of what's the next surprise," said one source. "Nobody's out of the woods yet." In the end, limited resources may force the Pentagon to embrace more efficient warfighting alternatives than those currently fielded or in the planning books. But for this week, at least, few at the Defense Department have a clear view as to how to get there, according to civilian and military officials. -- Elaine M. Grossman Reference #2 For Rumsfeld, Many Roadblocks: Miscues -- and Resistance -- Mean Defense Review May Produce Less Than Promised By Thomas E. Ricks, Excerpts: Yet six months into an administration that campaigned on a promise to rebuild the military, Rumsfeld's ambitious plans are under fire from all sides. Even before Rumsfeld has reached any final conclusions, Congress has made it clear that it would resist even modest cuts in troops and traditional weapons systems. Conservatives have howled that the Defense Department is not getting the money it needs from the White House. And the top brass has proven resistant to his direction. ... The defense review is likely to produce far less than once was promised. The lesson of Rumsfeld's return, some say, is that reforming today's military establishment may be impossible unless it is the White House's top priority. ... If Rumsfeld made miscalculations along the way, it was only part of the problem, according to many people outside the Pentagon. A more significant obstacle, that group says, is a military brass made up of generals and admirals wedded to existing weapons systems, troop structure and strategy. Seaquist, the former Pentagon policy aide, argued that "the military leaders were completely unprepared to offer any new thinking." In fact, said Newt Gingrich, the former speaker of the House and a longtime advocate of military transformation, the current tensions with the Joint Chiefs should be read as signs of progress. "If he were running a happy Pentagon right now, that would mean you had a guy throwing money at the past," he said. Reference #3 Rumsfeld Promises Change In Strategy, But Analysts See Little Difference Sharon Weinberger, ... Cindy Williams, a senior fellow of the Security Studies Program at MIT, said, "it looks to me like they may be putting a Band-Aid of some modern things over yesterday's force structure. That just doesn't make sense to me. If you want to bring the forces into the modern world, you have to make some more dramatic changes. "Almost every item on their shopping list today was put on in the 1970s," Williams said. "To imagine that we need every one of those items, makes no sense to me." Reference #4 Effort To Remake Military Erodes Into War Over Turf By Otto Kreisher, The goal was ambitious: reshape the military for the challenges of a new era. But it's running into the realities of the Pentagon, as protracted infighting among the military branches over their roles and limited defense dollars appears to be stalemating several Pentagon reviews of potential reforms. ... Andrew Krepinevich, director of the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, who worked on one of Rumsfeld's reviews, said the services' responses to new conditions seem to be more of the same. " 'Give us any threat . . . the force is the same,' " he said of the services' proposals. ... "The Navy has had problems selling what it has done . . . in the arena of transformation," said a congressional defense analyst who spoke on the condition he not be identified. "The Air Force view . . . is so well-defined that it can take a program conceived in the Cold War, such as the F-22, and show how it fits into a new concept." Reference #5 Bush's 'Strategy First' Vow Scrapped, Review Officials Say Rowan Scarborough, What began as a pledge to break with the past and reshape the military to fit a specific strategy has regressed to the Pentagon's usual practice of sizing the military based on available tax dollars, say officials involved in the strategy review. |